The first “home” in Tokyo

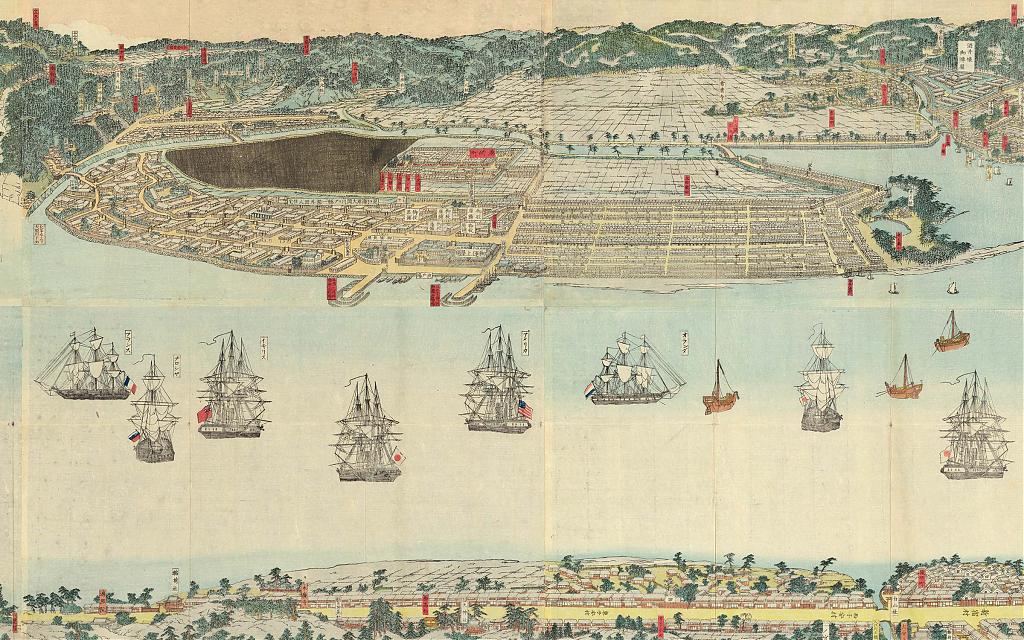

During the two centuries that the Dutch ran a trading station in Japan, there was never a Dutch residence in the Shogun’s capital. When the chief agents of the Dejima trading station visited, they stayed at the Nagasakiya Inn, in Edo’s Nihonbashi area. Commissioner Donker Curtius, being a diplomat, was accommodated at Saiōji Temple, and at Shinpukuji Temple in Atagoyama Shita when he negotiated a commercial treaty between March and June 1858.

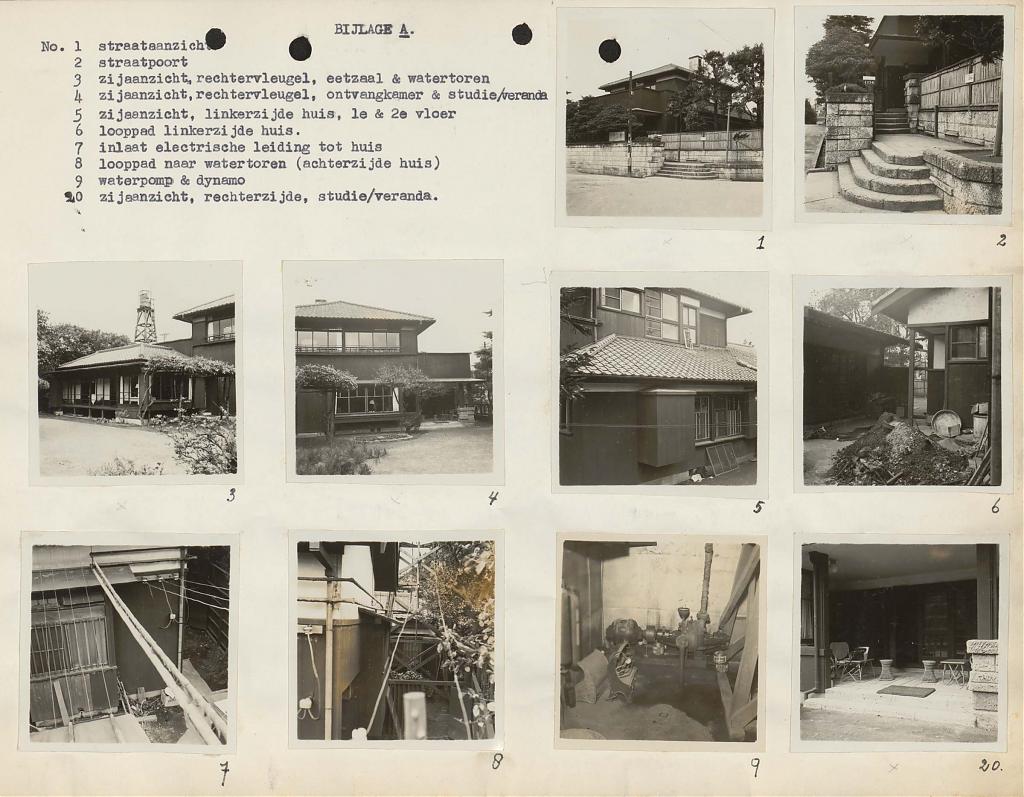

(Utagawa Hiroshige, woodblock print, ink on paper, 131004-0112-OS, MeijiShowa. Detail.)

It was this treaty that for the first time allowed the Netherlands to appoint a diplomatic agent to stay in Edo, thereby making it possible to create a permanent legation. Signed on August 18, 1858, it came into effect on July 4, 1859.

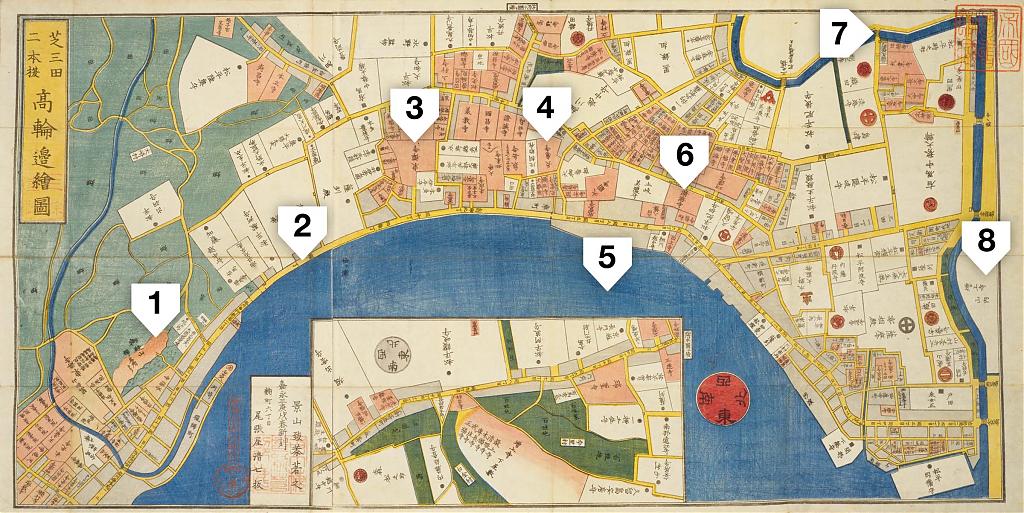

Soon after, vice-consul Dirk de Graeff van Polsbroek rented and furnished the Chō’ōji Temple (長応寺) for an expected visit by Donker Curtius. It was located on a hill in the Takanawa district, with a beautiful view of Edo Bay. Because of fears of attacks by samurai opposed to the opening of Japan, the shogunate had fortified the temple. The grounds were heavily guarded by Japanese soldiers.

Just as the Dutch traders had been at Dejima, De Graeff van Polsbroek was a privileged prisoner. But he didn’t mind. He enjoyed the peace of mind.1

That temple was completely surrounded by a high double palisade, between which patrols were made all night long. At the entrance and exit there was a guardhouse. I did not mind this. On the contrary, I found it wonderfully quiet and safe.

In spite of all these preparations, Donker Curtius remained at Dejima. Chō’ōji, however, did not go unused. According to De Graeff van Polsbroek’s memoirs, he regularly stayed here when he visited Edo to arrange affairs with the Japanese government.2

Consul General Jan Karel de Wit, who replaced Donker Curtius in 1860, also remained at Dejima. He visited Edo only four times during his almost three-year term in Japan. During his first and last visit he appears to have stayed at Chō’ōji for several weeks, but his second visit was a brief day trip, while he stayed for only three days on the third one.3

It is remarkable that De Wit decided to stay in far-away Nagasaki while the other treaty powers opened legations in the capital. What may have played a role is that each visit east was marked by terrifying violence. Dutch-American interpreter Henry Heusken was assassinated, the British legation was attacked twice, there was an attempted assassination on Rōjū Andō Nobumasa, one of the highest-ranking Japanese government officials, and a British trader was hacked to death while traveling on the Tokaido.

But likely more important was that the Dutch East Indies Government seemed unwilling to bear the cost of a consulate in Edo, and would not provide a warship for protection.4

As a result, De Wit even gave evasive responses when the Japanese government introduced plans to build more secure foreign legations at the Gotenyama area in Edo. He did however visit the proposed location on his second visit to Edo.

As it happens, the Gotenyama plan never came to fruition. In January 1863, the British legation here was burned down by samurai from the Chōshū domain while it was still under construction. The development was eventually given up.5

During De Wit’s term as consul general, De Graeff van Polsbroek—the de facto Dutch diplomatic representative in Edo—also seems to have barely stayed at Chō’ōji. In his memoirs, he wrote how he visited Edo on exhausting day trips:6

Repeatedly, with or without instructions from Consul General De Wit, I visited the Gorōjū [Council of Ministers] in Edo. Because of the anarchy in that city, the trips were surprisingly riveting, exhausting, and also extremely dangerous. The horseback ride there, at a brisk trot, lasted four hours. I changed clothes at the Dutch Legation in Edo, mounted another horse and reached the Gorōjū in an hour. The meeting lasted an hour, and I returned in the same way. So, I would be on horseback for ten hours. Coming home, I was often too exhausted to eat, and after taking a bath, went to bed.

Chō’ōji was occasionally made available by De Graeff van Polsbroek to other diplomats. Swiss politician Aimé Humbert (1819–1900) stayed here twice during his 1863–64 mission. Assisted by De Graeff van Polsbroek, he negotiated with Japanese government officials in Edo to conclude a treaty for Switzerland.

Thanks to the Swiss diplomat, who wrote that he would have gladly spent the summer months there, we have a beautiful description of the temple:7

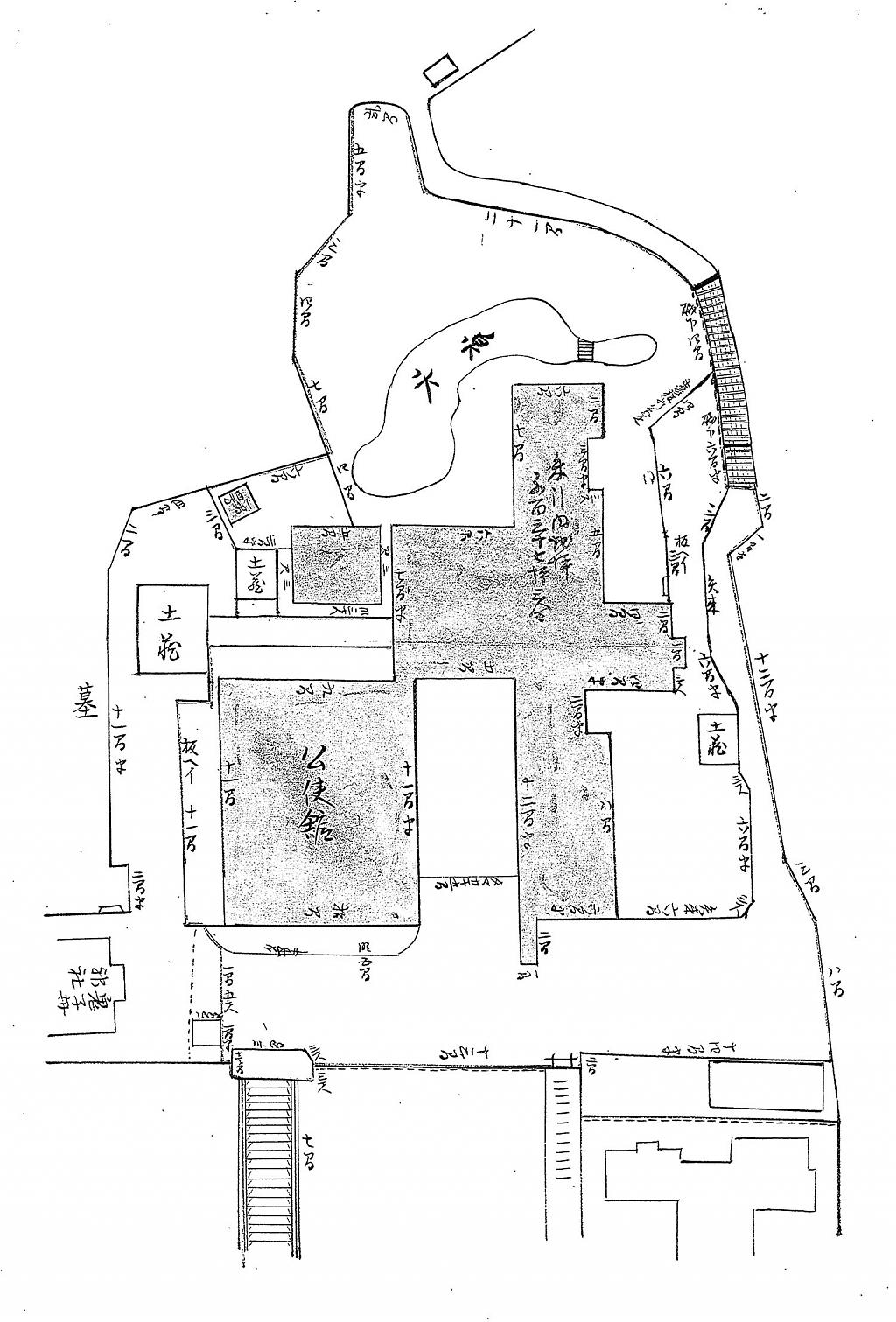

As this small abandoned temple is surrounded on all sides by other sacred places almost as solitary, one finds there the calm of the countryside near the liveliness of the large streets of the city. The road that leads to it from the Tokaido is partially cut into steps. Convent walls and a large black gate, topped by a roof, announce the entrance of the legation. The old cloister courtyard is bordered on two sides by wooden buildings, including a porter’s lodge, a guardhouse, horse stalls and a feed store. At the end of the courtyard, in front of the entrance, a large staircase of about twenty steps made of granite slabs, leads to an open area. On the right, another guardhouse, and on the left, the dwellings of monks. Finally, above this open space, a staircase that is narrower and shorter than the first, leads to the garden in front of the temple. A third guardhouse is installed there, at the foot of the poles where the flags of Holland and Switzerland fly.

Humbert then describes his meeting with the guards and the “mass of buildings, roughly in line with the flagpoles.” One end of these buildings was used as a kitchen, a photography workshop, and a display area for products introduced by local businessmen.

The other end, which extended into a semicircular enclosure behind the temple, consisted of a living room, a bedroom, and a dining room, all surrounded by an open gallery. This was the most peaceful and coolest part of the temple according to Humbert, and seemingly his favorite:

A pond lined with iris and lily pads occupies the center of the enclosure; it is fed by a spring which oozes out of a nearby cave lined with climbing plants. Next to this cave, in a niche surrounded by foliage, one can see an ancient sandstone deity, which still has its small altar and its torii. A rustic bridge over the stream leads to a path that winds through the trees and rocks, to the upper palisades of the enclosure. There, under a shelter of pines and laurels, a resting place has been carved from which the view dominates the gardens and buildings of Tjoôdji, and the harbor and the forts that protect it. At sunset, this little picture is full of charm. The sky and the bay come alive with the richest colors. The foliage of the hills shines with a sudden illumination. The pond is colored with purple hues. Then the shade invades the green enclosure and gradually covers the groups of trees which surround it. The birds of the beach come in great numbers to seek shelter there. Soon, the clumps of foliage are contrasted in black against the silvery sky, and the pond reflects, like ice, the trembling rays of the stars.

In September 1865, De Graeff van Polsbroek requested that the Japanese government make Chō’ōji habitable.8 Plans for enlargement were submitted in January and construction was started around summer.9

Chō’ōji may have been used more often after these improvements were completed. But if so, this use was brief in duration. De Graeff van Polsbroek no longer used the temple after December 1867, and the rental agreement was ended in June 1870.10

Significance

The treaty signed in 1858 allowed the Netherlands to have a permanent legation in Edo. Yet, it has become clear from this study that, though called a legation, Chō’ōji essentially functioned as a convenient branch office for occasional use. The real legation was at Yokohama’s Benten.

This is affirmed by what happened after De Graeff van Polsbroek’s departure in 1870. His successor, Minister Resident Frederik Philip van der Hoeven (1832–1904), immediately informed the Japanese government that Chō’ōji was no longer needed.11

Chō’ōji was nonetheless significant. It symbolically represented the Dutch presence in the Japanese capital during a period when anti-shogunate forces violently advocated the expulsion of foreigners. It deserves to be remembered as having played an important role in Dutch diplomatic history in Japan.

Sadly, this role turned out to be ruinous to the temple itself. It could no longer be used for religious activities and lost many parishioners. By the end of the century, Chō’ōji was sold. The proceeds were used to start a farm in Hokkaido.12 Where it once stood, nothing remains of the temple, nor of the Dutch legation.

A new start

It took two decades before a return was being considered to Tokyo, as the city was now called. In 1881, the former chief agent for Japan of Dutch trading giant NHM, Joannes Jacobus van der Pot (1843–1905), was appointed minister resident.

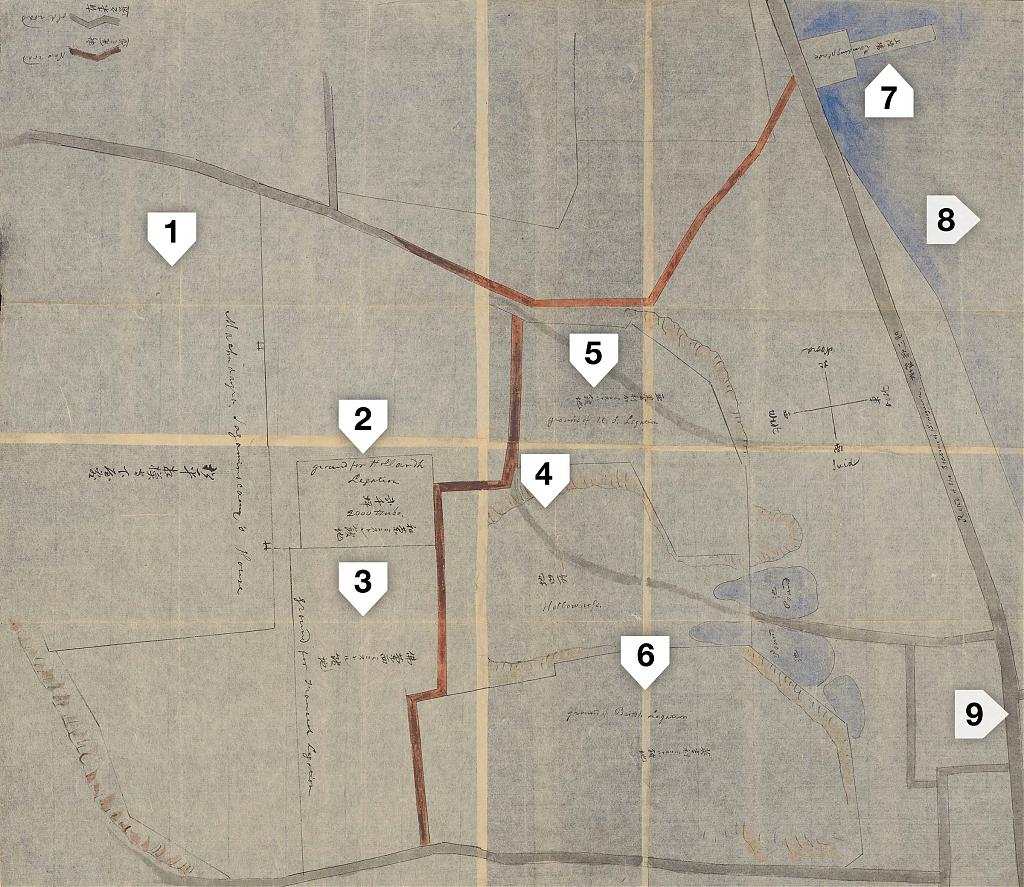

Having lived in Japan for at least a decade, Van der Pot knew the country extremely well and quickly launched a search for a new location in Tokyo. In July, almost immediately upon his appointment, he approached the Japanese Minister of Foreign Affairs about a plot in Tokyo for the Legation of the Netherlands. He wrote the minister that he envisioned “a permanent residence in Tokio.”13

Only a few weeks later, Van der Pot requested permission to rent a lot he had inspected at Shiba Kiridōshi (later renamed Sakae-cho, and now known as Shibakōen). None of the lots that he inspected had a house suitable for a legation, so he had selected a place that he considered “convenient for the purpose.”

“The bungalow at present standing on the front lot can be removed to the rear and used as a house for the secretary of [the] legation, while there is in front plenty of space to allow me to build a two stories [sic] brick house,” he wrote.14

Shiba Kiridōshi was an attractive location. It was surrounded by temples, and located just a short stroll from the magnificent Zōjōji Temple, last resting place of seven shoguns.

The area was known for its many trees and beautiful gardens. The 1890 edition of the respected Keeling’s Guide to Japan described the area in glowing terms:15

Shiba (Grass-plot). May be called the garden of Tokio; the roads are clean, wide and well laid out, many trees are planted on both sides of the road, affording delightful shade. In pretty gardens priests with shaved heads and wearing their sacerdotal robes are met with at every turning; but the chief attraction of Shiba is its temples, the most celebrated among them being the Zojoji. … Space not allowing a detailed account of many interesting and curious things to be seen at the different buildings in these grounds, we can not speak of the ornamental ceilings, of the panels artistically wrought in arabesques and high-relief, of the monolith lavatory, of the monumental urn or the depository of sacred utensils, but leave the visitor to survey and admire everything at his leisure.

It took until March 1883 before the legation was able to sign the contract with Tokyo Prefecture.16 But there were still more negotiations to come. The area turned out to be too small for all the needed buildings, and more land had to be acquired. This was completed in 1886.

In November of that year, Secretary Léon van de Polder was able to move in. Minister Resident Van der Pot followed in April 1887. Almost six years after he first approached the Japanese government, the legation had finally completed its move from Yokohama to Tokyo.17

Although the Dutch government was paying the rent for the land—in 1895 an adjusted landlease contract was concluded between the Japanese and Dutch governments—the buildings belonged to Van de Polder and Van der Pot. The Dutch government finally purchased the buildings in 1916, three decades after moving in.

The documentation of the sale, and comprehensive improvements carried out in 1919, lists the following buildings: the two-story legation building (No. 1), the seven-room secretary’s residence (No. 2), the joint interpreter and chancellor’s residence (No. 3), as well as a kitchen, servant quarters, two outhouses, and the gate keepers’ lodgings.18

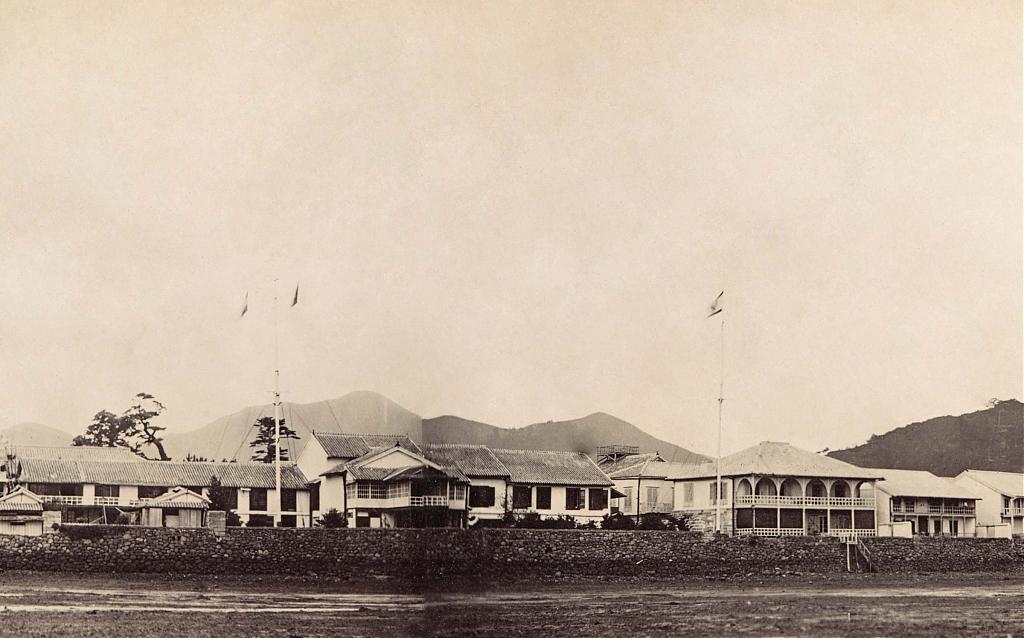

It is not yet known what all the buildings looked like, or who originally designed them. So far, this study has only found a few photos of the legation building.

Disaster

Unfortunately, the investments of 1916 and 1919 did not last very long. On Saturday, September 1, 1923, a massive earthquake devastated Tokyo, Yokohama, and their surroundings. The magnitude 7.9 Great Kantō Earthquake caused the 121-ton Great Buddha statue in Kamakura—over 60 km (37 mi) from the epicenter—to shift almost 60 centimeters.

The disaster killed or left unaccounted for an estimated 105,000 people, including former Counselor Van de Polder and his wife, Vice-Consul Visser in Yokohama, and five other Dutch nationals. Over 370,000 homes were lost, and 1.9 million people became homeless.

Tiles had fallen off the roofs, the chimneys had broken off, and there were cracks in the plaster, but the Dutch legation buildings in Shiba miraculously survived the tremors. However, the real danger was still to come. Immediately after the initial earthquake, fires swept across the disaster area, some of them developing into firestorms. These fires would actually cause 87% of the fatalities.19

Dutch envoy Jean Charles Pabst had only arrived in mid-June. But he had previously worked in Japan and was keenly aware of the dangers of fire in tightly built cities of wooden houses with paper doors and straw mats. He kept a close watch all day.20

In the evening I personally made sure that the neighborhoods around the mission were completely calm. No one there was thinking of fire, but for fear of new earthquakes they were getting ready to spend the night under the open sky. Around midnight I saw a fire, which was raging about 3/4 hours north, northwest of the legation, gradually spreading. It depended entirely on the direction of the wind whether this could cause danger to our buildings. After midnight, the fire spread in our direction. But the danger did not yet seem great, because the legation buildings stood completely in the open, and were partly covered against sparks by high trees on the side of the fire. Moreover, there was plenty of time to keep the roof wet and clear some dangerously situated buildings which could spread the fire to us.

His precautions were in vain. At five in the morning, the legation building caught fire and burned down. All of his furniture, which had arrived only two days prior, was lost.21 As was a significant part of the legation’s archives.

The secretary’s residence (No. 2) survived the inferno. This was mainly thanks to the resolute action of former chauffeur Uda, Pabst wrote in a report to the Dutch Minister of Foreign Affairs. Although it had been “some time” since he was employed by the legation, he nonetheless showed up “to help out if necessary.”22

Going back and forth on the roof, Uda managed to defuse the falling sparks, so that the building was saved, and the State of the Netherlands was spared great loss. It seems to me that Uda has deserved a reward for this and I therefore recommend him to Your Excellency for a Royal decoration, which in this case could consist of the Silver Medal in the Order of Orange-Nassau.

Having done all he could at the legation, Pabst took the lead in the rescue efforts of the Dutch community. According to a contemporary report in the Bataviaasch Nieuwsblad, one of the largest daily newspapers in the Dutch East Indies, Pabst drove to Yokohama as far as he could, then boarded a Japanese destroyer which took him to Yokohama, which had been completely flattened by the disaster.23

While walking in the dark, he fell from a bridge without railings, resulting in a sprained ankle and bruised ribs. Some two weeks later, he nevertheless managed to travel to Kobe where most of the survivors had sought shelter, to conduct the relief efforts there.

“A you can see,” he wrote his sister, “I have had more adventures in ten days as a diplomat than in my thirty-year military career. If this continues, I have a long road ahead of me.”24

A new legation building

Provisional repairs were made on buildings No. 2 and No. 3, and barracks were constructed to replace the burned down servants’ quarters. Pabst moved into No. 2, which he shared with Secretary Willem Johan Rudolf Thorbecke (1892–1989), grandson of one of the most important politicians in Dutch history. The chancellery was temporarily housed there as well.

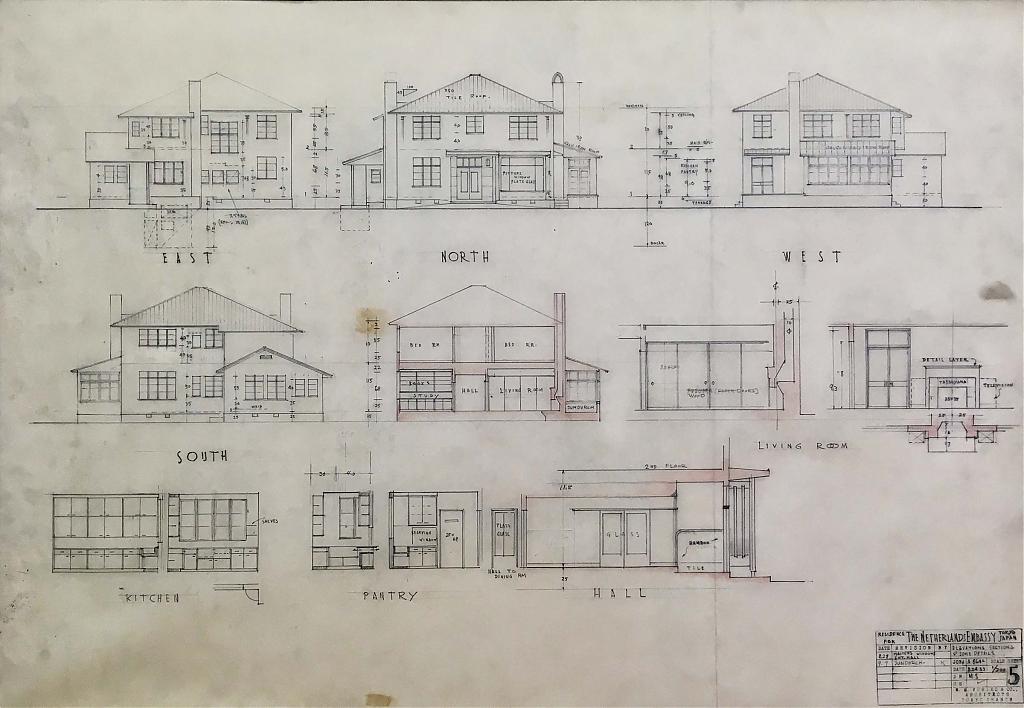

American architect James McDonald Gardiner (1857–1925) designed the new legation building. After his death in 1925, Japanese architect Kanbayashi Keikichi (上林敬吉, 1884–1960) took over. Shimizu-Gumi (present-day Shimizu Corporation) was contracted to construct the building.

The plan for the new No. 1 included a main building, with an attached chancellery, a kitchen, and servants’ quarters. The two-story building featured a basement and attic. Because of the experience of the Great Kantō Earthquake, experts advised the use of reinforced concrete for the new building rather than wood, as was done with the burned down building.

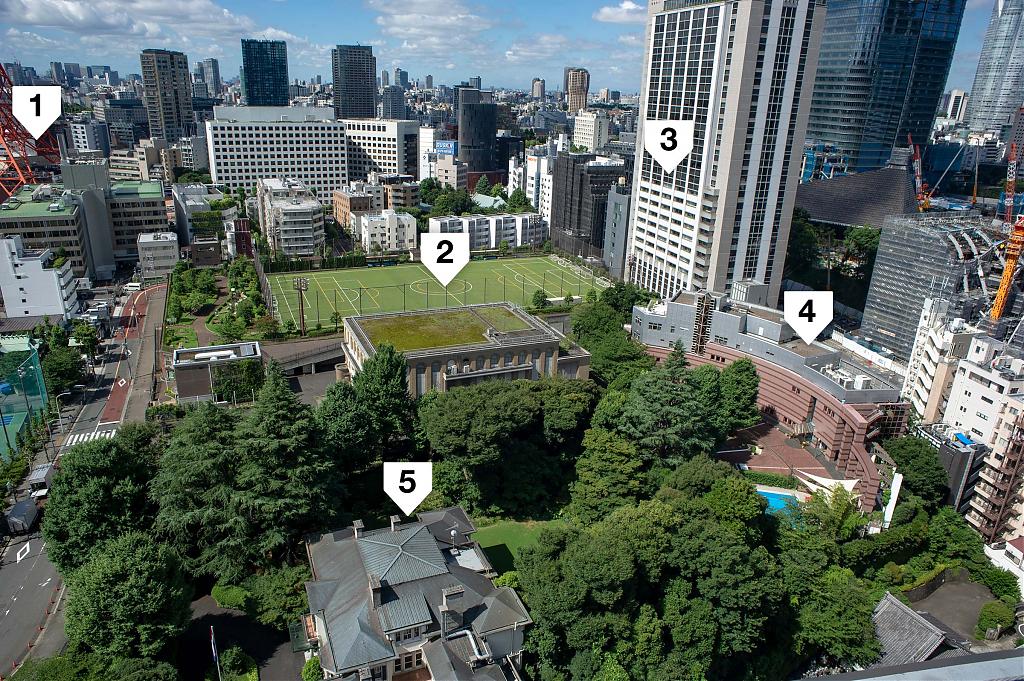

Completed in August 1928, several extensions were added and removed over the years. But the building essentially remains as it was built. Today it is used as the Official Residence of the ambassador.

Documents from 1940 also mention a building No. 4., vacated and needing repairs. It featured an entrance hall, dining and drawing rooms, a bedroom, a sitting room, a veranda, a bathroom and toilets, a kitchen and pantry, a Japanese-style bedroom, and a lodging for servants. It is as yet unknown when this building was built, where on the premises it was located, how it was used, or what it looked like.25

Second World War

After the Imperial Japanese Navy attacked Pearl Harbor in December 1941, the Dutch government in exile declared war on Japan. The legation of the Netherlands was immediately sealed off by the Japanese authorities, its diplomats becoming prisoners in their own homes.

The Dutch government requested neutral Sweden become the Protecting Power and its diplomatic representative in Japan, the first country to do so. Swedish Minister Widar Bagge (1886–1970) managed to speak to Pabst on December 10. A report of the meeting was sent via Stockholm to London, where the Dutch government in exile was based.26

Thanks to the efforts by the Swedish legation, most Dutch nationals were evacuated on July 30, 1942. Bagge now arranged for former Japanese staff to occupy and take care of the Dutch legation buildings. This arrangement failed, so Swedish legation members Erik von Sydow (1912–1997) and Nils E. Ericson moved in to protect the legation. This ended up working well for both the Swedish legation members and the Dutch government.27

Swedish businessman Carl-Erik Necker (1910–2003), who started working at the Swedish Legation in 1943, wrote in his memoirs about an episode at the Dutch Legation during one of the earliest WWII bombing raids on Tokyo:28

It became worse on June 16, 1944, the “old King’s” birthday, when the first legation secretary Erik von Sydow and his wife had invited the diplomatic corps in Tokyo to the former Dutch embassy, where they then lived. The party began with cocktails out in the beautiful garden, and just as the first glass was drunk, everyone felt a strong tremor. It may not have been very noticeable outdoors, but when we then entered the stately dining room, everyone saw the beautiful crystal chandeliers shake so much that one thought they would fall down.

Overcoming war

By the end of the war, in August 1945, more than half of Tokyo had been flattened by American air raids. Yet, the Dutch legation building, and the legation and consulate archives, somehow survived. The three other buildings on the Dutch legation grounds had burned down.29

Lieutenant Admiral Conrad Emil Lambert Helfrich (1886–1962), of the Royal Netherlands Navy, signed the Japanese Instrument of Surrender on behalf of the Kingdom of the Netherlands aboard the battleship USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay on September 2, 1945. The next day, this leading Dutch naval figure of World War II visited the Dutch Legation in Tokyo. He handed Swedish Legation Counselor Ericson a Dutch flag which was immediately raised there.30

We also visited the Dutch embassy building in Tokyo. It was in good condition, and well cared for by the Swedish Legation during the war. I found numerous packed suitcases and boxes of the former deceased envoy, General Pabst, waiting to be transported to the Netherlands. And I had a Dutch flag hoisted, kindly donated by the captain of the Dutch hospital ship Tjitjalengka, anchored in Tokyo Bay.

The Dutch government decided to establish a Dutch Military Mission in Tokyo in February 1946. It was headed by General Wijbrandus Schilling (1890–1958).31 Johan Burchard Diederik Pennink (1886–1967), consul general in Kobe before the war, was appointed as diplomatic representative.

Schilling arrived in Tokyo on May 20, 1946 and moved into the Imperial Hotel where he would stay until his departure in 1948. Pennink arrived several days later. He stayed at the Imperial for a few days before moving into the legation building with his wife.32 Here, in late August 1946, General Douglas MacArthur (1880–1964), who oversaw the occupation of Japan from 1945 to 1951, toasted to the health of Dutch Queen Wilhelmina (1880–1962) on the celebration of her birthday.

Over the next few years, mission personnel were housed at several locations in Tokyo, provided through military procurement. One of the more interesting locations was “Holland House,” the former mansion of the Hosokawa family, a prominent samurai clan during the Edo Period (1603–1868) who became influential nobility in the Meiji period (1868–1912).

During the Korean War (1950 to 1953), the Dutch military used it for the rest and recuperation of soldiers. The building in Tokyo’s Mejirodai still stands. Since 1955 it has housed Wakeijuku, a dormitory for male students.

The military mission was replaced by a civil one in September 1948. First under deputy head Evert Joost Lewe van Aduard (1912–1975), and from January 1949 under Hendrik Mouw (1886–1970).

The Treaty of Peace with Japan came into force on April 28, 1952. Almost simultaneously, the treaty was ratified by the Dutch parliament and diplomatic relations between Japan and the Netherlands were restored. As a result, Petrus Ephrem Teppema, who had replaced Mouw in 1951, became the first Dutch ambassador in Japan. The former legation was now an embassy.33

The question of housing

The civil mission had continued to use the housing originally provided by the U.S. occupying forces. So, when the treaty ended military housing procurement, the embassy faced a severe housing crisis.34

Some temporary solutions were arranged. For example, three secretaries staying in Holland House were moved to rooms at the Masonic Building near the embassy. While the rental term for the house used by Counselor Herman Hagenaar (1908–1986) and his family—in effect the replacement of the burned down House No. 2—was extended by a year. This was very much against the will of the owner, who managed to charge an extortionate rate.35

A more lasting solution was needed quickly, so the embassy commissioned famed American-Japanese architect William Merrell Vories Hitotsuyanagi (1880–1964) to design replacements for the three buildings burned down in 1945. Vories did so, but went a step further. He also suggested and designed a plan for an apartment building to be erected on the embassy grounds instead.36

Careful consideration of the entire situation leads us to the conviction that it would be unwise to attempt to crowd three or four separate residences, with as many garages (or a single large one), and all service quarters, into the available space. In fact, it has become questionable, in a city as large as Tokyo, to build separate residences, with individual gardens. The logical conclusion is that it will be highly advantageous to erect modern Apartments for the Embassy staff.

The embassy proceeded on this course. But just as construction was about to start—the area of the embassy grounds where the building was to rise had been leveled already—the plan was scrapped by the Dutch government.

Instead of the apartment building, a new residence for the counselor was built to replace the lost building No. 2. This is believed to have been completed in early 1954, and was extended around 1956. Unfortunately, this study has not yet been able to find clear photographs of this building. But there are design plans, as well as aerial photos of the property, taken just a few years after the villa was completed.

The present

Over the following decades, the work of the embassy increased substantially. By the late seventies, it had become painfully obvious that the office wing of the main building was far too small. This was finally solved when a large five-story chancery, separate from the official residence, was opened in October 1991. Interestingly, it was constructed by Shimizu Corporation, the same company that built the legation building in 1928.

The fan shaped building, reminiscent of the shape of Dejima island, was designed by Dutch architect Hans van Os. The landscaping was done by Dutch environmental designer Karin Daan. She incorporated the old ginkgo trees that survived the 1923 disaster, to make them dominate a ginkgo leaf-shaped red square with white inlay in front of the building.

In a way, this new building echoed Vories’ plan as it was a modern multi-story building featuring apartments for staff members. The biggest difference was that it was mainly an office building. Still, one could say that, after almost four decades, Vories’ vision had been vindicated. Sadly, the villa he designed had to be torn down to make room for the new building.

The next important step in the history of the embassy came in 2005. That year, almost exactly 110 years after the adjusted landlease contract had been concluded, the Dutch government purchased the property from the government of Japan. Now, the embassy was ready for the future.

Postscript

After this research project was closed, photographs of the residence for the counselor from the 1960s were discovered.

| TIMELINE | |

|---|---|

| 1859 | Chō'ōji temple rented and furnished by vice-consul Dirk de Graeff van Polsbroek. |

| 1867 | December: Chō'ōji used for the last time by De Graeff van Polsbroek. |

| 1870 | June: Rental agreement with Chō'ōji is ended. |

| 1881 | July: Minister Resident Joannes Jacobus van der Pot approaches the Japanese Minister of Foreign Affairs about a plot in Tokyo for the Legation of the Netherlands. |

| 1887 | April: Van der Pot moves in. |

| 1923 | September: The legation building burns down because of the Great Kantō Earthquake. |

| 1928 | August: A new legation building is completed. |

| 1941 | December: The legation is sealed because of World War II. Swedish diplomats watch over the legation during the war. |

| 1946 | February: Johan Burchard Diederik Pennink, diplomatic representative of the Dutch military mission, moves into the main building. |

| 1952 | Diplomatic relations between Japan and the Netherlands are restored. The former legation becomes an embassy. Petrus Ephrem Teppema becomes the first Dutch ambassador in Japan. |

| 1991 | A large five-story chancery is completed. |

| 2005 | The Dutch government purchases the property from the government of Japan. |

Next: 5. Kobe-Osaka

What we still don’t know

(These questions are only shown on this site)

- Where in Tokyo was the vice-consulate and consulate located, and from when to when? (see 6. Other Locations)

- How many buildings were there on the embassy lot before WWII, when were they built, what did they look like, and how were they used? No photographs of these auxiliary buildings have yet been found.

Notes

- Footnotes are only shown on this site, not in the book.

- See the Notebook of this article for the raw data.

- See the Archive for some of the primary documents used in the study.

1 Moeshart, H.J. (1987). Journaal van Jonkheer Dirk de Graeff van Polsbroek 1857-1870. Assen/Maastricht: Van Gorcum, 54, 56.

2 ibid, 56.

3 Yokoyama, Yoshinori (1993) Dutch-Japanese Relations during the Bakumatsu Period: The Monthly Reports of J.K. de Wit, Tokyo: Journal of the Japan-Netherlands Institute, volume V pp. 1-260:

- First Visit: Arrival De Wit arrives in Yokohama on December 6, 1860, stays for five days, then leaves for Edo. “Daar Akabane, waar de Nederlandse Commissaris zijn verblijf heeft gehouden, door het Pruisische gezantschap ingenomen was, is nog een tempel Tsjio-odji genaamd afgestaan, welke niet ver van de overige legatie verwijderd, een zeer geschikt verblijf zal aanbieden, wanneer dezelve zoveel nodig en mogelijk voor bewoning naar de Europesche wijze ingericht zal zijn; het erf, waarop de priesters nog in klein bijgebouwen wonen is geheel van schuttingen omgeven en zes ambtenaren zijn er tot bewaking, die mij als geleide volgen zoo dikwijls ik uitga.” — Maandelijks verslag over December 1860 pp. 103.

- First Visit: Kanagawa On January 3, 1861, De Wit is in Kanagawa. Heusken is killed on the 15th, and the foreign diplomats moved from Edo to Yokohama around the 21st of that month. De Wit writes “bij mijne terugkomst te Kanagawa” on page 116, but it is unclear if he returned from Edo. — Maandelijks verslag over Januarij 1861 pp. 112.

- First Visit: Departure De Wit leaves Kanagawa for Dejima on February 17, 1861. — Maandelijks verslag over Februarij 1861 pp. 122.

- Request for Return of Temple “… bleek mij nu nog uit een bericht van den Waarnemend Vice Consul der Nederlanden te Kanagawa, dat de Gouverneur dier plaats hem verzocht had mij het verlangen der Japansche Regering mede te deelen om den tempel tot mijn verblijf te Jedo afgestaan terug te nemen, indien ik daarvan geen verder gebruik maakte.” — Maandelijks verslag over Maart 1861 pp. 127.

- Second Visit: Arrival De Wit arrives in Yokohama on July 3, 1861. The Tōzen-ji Incident took place on the night of July 5-6. — Maandelijks verslag over Julij 1861 pp. 149.

- Gotenyama as Alternative “De onzekerheid waarin ik ben in hoeverre der Nederlandsche Regering het verblijf van een Diplomatiek Agent te Jedo en de kosten van huur van zulk een gebouw zoude goedkeuren, heeft gemaakt dat ik vermeden heb een bepaald antwoord over deze gehele zaak te geven.” | “De uitnodiging om het terrein te komen bezichtigen had ik eene gereed aanleiding om af te wijzen door te zeggen dat ik niet naar Jedo konden gaan, zonder de eerbewijzen te ontvangen, die bij hunne terugkomst aan de Ministers van Engeland en Frankrijk waren vervelend.” — Maandelijks verslag over September 1861 pp. 165.

- Second Visit: Gotenyama Visit and Departure On October 10, 1861, De Wit visited Gotenyama in Edo to select an area for the legation. He returned to Yokohama the same day and left for Nagasaki the day after. “… maar de afgezonderde ligging van het terrein buiten de stad zal met de voorzorgsmaatregelen van wal en grachten te zeer den schijn van afsluiting blijven behouden.” — Maandelijks verslag over October 1861 pp. 167–168.

- Third Visit: Arrival De Wit arrives in Yokohama on January 22, 1862. — Maandelijks verslag over Januarij 1862 pp. 178.

- Third Visit: Arrival in Edo On March 15, 1862, De Wit visits Edo for a meeting with a Japanese government official. Chō’ōji is not mentioned, but it is likely that De Wit stayed here. — Maandelijks verslag over Maart 1862 pp. 193.

- Third Visit: Departure from Edo On March 18, 1862, De Wit returns to Yokohama. He leaves for Nagasaki four days later. — Maandelijks verslag over Maart 1862 pp. 196.

- Fourth Visit: Arrival De Wit arrives in Yokohama on June 10, 1862. He went to Edo the following day. It is unclear how long he stayed at Chō’ōji. — Maandelijks verslag over Junij 1862 pp. 210.

- Fourth Visit: Departure On November 22, 1862, De Wit returns to Nagasaki. — Maandelijks verslag over November 1862 pp. 238.

| Visit | Summary | Incidents |

|---|---|---|

| First | December 11, 1860: Arrival at Chō'ōji. Unsure how long De Wit stayed. Was in Kanagawa in early January. | Henry Heusken assassinated on January 15, 1861. |

| Second | October 10, 1861: De Wit visits Gotenyama, does not stay in Edo overnight. | First Tōzen-ji Incident on the night of July 5, 1861. |

| Third | March 15–18, 1862: In Edo. Report does not mention Chō'ōji, but it is likely that De Wit stayed there. | Attempted assassination of Rōjū Andō Nobumasa on January 15, 1862. |

| Fourth | June 11, 1862: Arrival at Chō'ōji. It is unsure how long De Wit stayed at Chō'ōji, but he returned to Nagasaki on November 22. | Second Tōzen-ji Incident on June 27, 1862. Namamugi Incident on September 14, 1862. |

- Because the temple was hardly used, the Japanese government sent De Graeff van Polsbroek a letter on March 15, 1861 explaining that the head priest wanted his temple back and suggesting to move the furniture to the Akabane guest house. De Graeff van Polsbroek rejected this. — 2.05.10.08 Inventaris van het archief van het Nederlandse Gezantschap in Japan, 1879-1890: 36 Correspondentie over gronden en eigendommen der Nederlandse regering te Yokohama (Benten), Yedo en Kanagawa. 1860-1877, 0147–0148.

4 Yokoyama, Yoshinori (1993) Dutch-Japanese Relations during the Bakumatsu Period: The Monthly Reports of J.K. de Wit, Tokyo: Journal of the Japan-Netherlands Institute, volume V pp. 12.

5 ibid, pp. 245: “Na het vernielen van het gebouw voor de Engelse Legatie bestemd heb ik een brief ontvangen van de Japansche Ministers, waarin zij mij onder mededeling van het gebeurde, hunne vrees te kennen geven dat de volksgeest wellicht tot erger moet overslaan, indien men er bij volhardde om de gebouwen voor de Legatiën op te richten op Goten-Jama, daar deze plaats van oudsher voor algemeene volks vermakelijkheden bestemd was, en mij verder voorstellen om in overleg met de overige Diplomatieke Agenten eene andere plaats hiertoe uit te kiezen.” — Maandelijks verslag over Maart 1863.

For more information, also see: United States, Department of State (1864). Papers Relating to Foreign Affairs: Accompanying the Annual Message of the President to the First Session of the Thirty-eighth Congress, Volume 2. U.S. Government Printing Office, 985–988.

6 Moeshart, H.J. (1987). Journaal van Jonkheer Dirk de Graeff van Polsbroek 1857-1870. Assen/Maastricht: Van Gorcum, 61. “Het jaar 1862 liep verder zeer geagiteerd ten einde. Herhaaldelijk bracht ik met of zonder last van de Consul-Generaal de Wit bezoeken aan de [Gorōjū] (Ministerraad) in Edo. De tochten waren verbazend aangrijpend, vermoeiend, tevens uiterst gevaarlijk wegens de anarchie in die stad. De rit ter paard derwaarts, op flinken draf, duurde vier uur. Ik verkleedde mij dan in de Nederlandse Legatie te Edo, steeg op een ander paard en bereikte dan in een uur de [Gorōjū]. Het onderhoud duurde dan een uur en keerde ik op dezelfde wijze terug. Tien uur had ik dus te paard gezeten. t’Huis komende was ik dan ook dikwerf te vermoeid om te kunnen eten en begaf ik mij na het gebruiken van een bad, naar bed.”

7 Humbert, Aimé (January 1867). Le Tour du monde: nouveau journal des voyages / publié sous la direction de M. Édouard Charton et illustré par nos plus célèbres artistes. Le Japon (pp. 289–336). Paris: Hachette, 300–303.

The Consul of Portugal also stayed at Chō’ōji. Letter dated January 16, 1866: 2.05.10.08 Inventaris van het archief van het Nederlandse Gezantschap in Japan, 1879-1890: 36 Correspondentie over gronden en eigendommen der Nederlandse regering te Yokohama (Benten), Yedo en Kanagawa. 1860-1877, 0143.

8 Nationaal Archief. 2.05.10.08 Inventaris van het archief van het Nederlandse Gezantschap in Japan, 1879-1890: 36 Correspondentie over gronden en eigendommen der Nederlandse regering te Yokohama (Benten), Yedo en Kanagawa. 1860-1877, 0142. Letter dated September 22, 1865, requesting the Japanese government to make Chō’ōji habitable. If not De Graeff van Polsbroek will build a house in Yokohama.

9 ibid, 0143. January 9, 1866: Plans for enlargement of Chō’ōji. This was described as a “new wing” or “new house” in different letters. It appears that it took until summer until construction was started.

- ibid, 0143 (right). In a letter dated November 5, 1866 permission is also requested to make changes to the room of the chancellor.

10 Japan Center for Asian Historical Records, B12082764300, 芝長応寺和蘭仮公使館地租家租徴収一件. Letter by De Graeff van Polsbroek dated February 7 1871 (0051–0052), states that he had not used Chō’ōji since December 1867. Another letter states that Chō’ōji was furnished for European use and could not be rented to Japanese.

11 Nationaal Archief. 2.05.10.08 Inventaris van het archief van het Nederlandse Gezantschap in Japan, 1879-1890: 36 Correspondentie over gronden en eigendommen der Nederlandse regering te Yokohama (Benten), Yedo en Kanagawa. 1860-1877, 0144 (right). Letter dated June 16, 1870: The legation no longer wishes to use Chō’ōji.

Also: Japan Center for Asian Historical Records, B13080024800, 各国往復国書 自安政五年至慶応四年/分割3 and B13090494400, 公使館/長応寺蘭国仮公使館一件 一 | 外務省外交史料館特別展示「幕末へのいざない」展示史料解説 外務省外交史料館別館展示室・平成28年10月11日~12月27日

12 When the samurai system was abolished in the early 1870s, it lost more parishioners. The proceeds were used to develop the Hokkeshū-Nojō farm in Teshio-gun, northern Hokkaido. In 1902, the temple was relocated to this farm. In 1907, a new Chō’ōji temple was also built in Koyama in Tokyo’s Shinagawa-ku. 林, 善茂(1963)法華宗農場顚末北海道大學 經濟學研究 12-2、北海道大学經濟學部、11–29. Also 品川史跡めぐり・長応寺(ちょうおうじ) 小 山 1-4-15 品川区政50周年記念誌 しながわ物語(品川区企画部広報広聴課)

13 Japan Center for Asian Historical Records, B12083356000, 1881年7月25日付和蘭公使ヨリ外務卿代理上野景範宛公使館地所之件ニ付依頼. Van der Pot’s name is also spelled as Johannes.

14 Japan Center for Asian Historical Records, B12083356100, 1881年8月19日和蘭公使ヨリ上野景範宛芝切通シニアル杉氏所有地所之件, 0012, 0013.

15 Farsari, A. (1890). Keeling’s Guide to Japan: Yokohama, Tokio, Hakone, Fujiyama, Kamakura, Yokoska, Kanozan, Narita … Yokohama: Kelly & Walsh, Limited, 57–59. Sadly, this was all bombed into oblivion during the Second World War.

16 Japan Center for Asian Historical Records, B12083356100, 1881年8月19日和蘭公使ヨリ上野景範宛芝切通シニアル杉氏所有地所之件, 0080.

17 Japan Center for Asian Historical Records, B12083356300, 一般/分割1.

The lot was again enlarged in 1895. Japan Center for Asian Historical Records, B12083356400, 一般/分割2.

18 Nationaal Archief. 2.05.115 Inventaris van het archief van het Nederlandse Gezantschap in Japan (Tokio), 1923-1941: 123 Stukken betreffende de Nederlandse gezantschapsgebouwen in Tokio. 1914-1927.

19 武村 雅之。過去の災害に学ぶ(第13回) 1923(大正12)年関東大震災 – 揺れと津波による被害 - 広報 ぼうさい No.39 2007/5. Also 鹿島小堀研究室の研究成果を基に、理科年表が関東大震災の被害数を80年ぶりに改訂

20 Nationaal Archief. 2.05.115 Inventaris van het archief van het Nederlandse Gezantschap in Japan (Tokio), 1923-1941: 123 Stukken betreffende de Nederlandse gezantschapsgebouwen in Tokio. 1914-1927, 0723–0731.

“De meest nabijzijnde brand woedde op minstens 1/2 uur gaans, zodat voorlopig geen gevaar bestond. In den avond overtuigde ik mij persoonlijk, dat de wijken rond het gezantschap gelegen volkomen rustig waren, dat niemand daar aan brand dacht, maar dat men uit vrees voor nieuwe aardschokken zich gereed maakte den nacht onder den blooten hemel door te brengen.”

“Tegen middernacht tusschen 1 en 2 Sept. zag ik een brand, welke op ongeveer 3/4 uur afstand noord, noordwest van het gezantschap woedde, gaandeweg zich uitbreiden [sic]; het hing geheel van de richting van den wind af, of hieruit gevaar voor onze gebouwen kon ontstaan. Na middernacht breidde de brand zich in onze richting uit, maar het gevaar scheen nog niet groot, omdat de gebouwen van het gezantschap geheel vrij staan, aan de zijde van den brand gedeeltelijk door hooge boomen tegen vonken gedekt waren en bovendien, omdat alle tijd bestond tot nathouden van het dak en opruiming van eenige gevaarlijk staande gebouwtjes, die den brand naar ons konden voortplanten.”

…

“Onder die omstandigheden was het lot der gebouwen van het gezantschap niet twijfelachtig; toch duurde het tot ongeveer 5 uur in den morgen van 2 Sept, vóórdat het hoofdgebouw vlam vatte.”

21 Stolk, Dr. A.A.H. (1997). Jean Charles Pabst: Diplomaat en Generaal in Oost-Azië 1873-1942. Zeist: Dr. A.A.H. Stolk, 46.

22 Nationaal Archief. 2.05.115 Inventaris van het archief van het Nederlandse Gezantschap in Japan (Tokio), 1923-1941: 123 Stukken betreffende de Nederlandse gezantschapsgebouwen in Tokio. 1914-1927, 0723–0731.

“Het secretarisgebouw is gespaard gebleven, en dat zulks voor een groot deel te danken is aan het cordate optreden van den vroegere chauffeur Uda van de Heer Thorbecke, die, hoewel sedert eenigen tijd niet meer bij dezen in dienst, toch op het gezantschap verschenen was om zoo nodig te helpen. Op het dak heen en weer gaande, wist Uda de neerkomende vonken onschadelijke te maken, waardoor het gebouw ten slotte behouden werd en den Staat der Nederlanden groot verlies bespaard is gebleven. Het komt mij voor, dat Uda voor een en ander een belooning verdiend heeft en ik veroorloof mij dan ook hem bij Uw Excellentie aan te bevelen voor een Koninklijke onderscheiding, welke in dit geval in de zilveren eremedaille der oranje-Nassau-Orde zou kunnen bestaan.”

23 Bataviaasch Nieuwsblad (1923-10-01), De aardbeving in Japan: Het lot der Hollanders. “Later heeft hij zich zover mogelijk met zijn auto begeven in de richting van Yokohama en is toen met een Japanschen destroyer verder naar Yokohama gegaan. Het deed goed om te zien hoe kalm de heer Pabst daar alles in Yokohama regelde.”

24 Stolk, Dr. A.A.H. (1997). Jean Charles Pabst: Diplomaat en Generaal in Oost-Azië 1873-1942. Zeist: Dr. A.A.H. Stolk, 46. “Je ziet dat ik in tien dagen als diplomaat meer avonturen heb gehad dan in mijn dertigjarige militaire loopbaan. Als dat zo doorgaat, staat mij nog heel wat te wachten.”

Also: Nationaal Archief. 2.05.115 Inventaris van het archief van het Nederlandse Gezantschap in Japan (Tokio), 1923-1941: 123 Stukken betreffende de Nederlandse gezantschapsgebouwen in Tokio. 1914-1927.

Nationaal Archief. 2.05.115 Inventaris van het archief van het Nederlandse Gezantschap in Japan (Tokio), 1923-1941: 98 Pabst, J.C., 1935-1941, 0386.

25 Nationaal Archief. 2.05.115 Inventaris van het archief van het Nederlandse Gezantschap in Japan (Tokio), 1923-1941: 124 Stukken betreffende onderhoud van de gezantschapsgebouwen. 1938-1940, 0001–0002.

26 Lottaz, Pascal, Ottosson, Ingemar, Edström, Bert (2021). Sweden, Japan, and the Long Second World War: 1931–1945. New York: Routledge, 134.

27 ibid, 138.

28 Necker, Carl-Erik (1997) Minnen från krigsåren i Japan, Hikari Skandinavisk-japansk litteraturtidskrift Vol-3, Nr. 2.

29 Nationaal Archief. 2.12.44 Inventaris van het archief van het archief van Luitenant-Admiraal C.E.L. Helfrich, 1940-1962: 13 Stukken betreffende de aanwezigheid van Helfrich bij de ondertekening van de Japanse overgave in Tokio, september 1945, 0006.

30 Helfrich, C.E.L. (1950). Memoires van C. E. L. Helfrich Luitenant-Admiraal b.d. Tweede Deel: Glorie en tragedie. Amsterdam/Brussel: Elsevier, pp 224 (3 september 1945). “Wij bezochten ook het Nederlandsche gezantschapsgebouw te Tokio. Het was in goede staat, en gedurende de oorlog goed verzorgd door het Zweedse gezantschap. Ik vond er talrijke gepakte koffers en kisten van de vroegere, overleden gezant, generaal Pabst, welke op vervoer naar Nederland wachtten. En ik liet een Nederlandse vlag hijsen, welwillend afgestaan door de gezagvoerder van het in Tokiobay liggende Nederlandse hospitaalschip Tjitjalengka.”

31 Van Poelgeest, Lambertus (1999). Japanse Besognes: Nederland en Japan 1945–1975. ‘s-Gravenhage: SDU, 122.

32 ibid, 126.

33 ibid, 130.

34 Nationaal Archief. 2.05.116 Inventaris van het archief van de Nederlandse diplomatieke vertegenwoordiging in Japan (Tokio), 1946-1954: 434 Stukken betreffende de behuizing van Nederlands ambassadepersoneel in Tokio 1952-1953, 0062, 0078, 0084.

35 ibid, 0013, 0036–0042.

36 Nationaal Archief. 2.05.116 Inventaris van het archief van de Nederlandse diplomatieke vertegenwoordiging in Japan (Tokio), 1946-1954: 425 Stukken betreffende de bouw van de Nederlandse ambassadegebouwen in Tokio 1952, 0047. Merrell Vories Hitotsuyanagi to Netherlands Ambassador, May 1, 1952.

Published

Updated

Reference for Citations

Duits, Kjeld (). 4. Edo-Tokyo, From Dejima to Tokyo. Retrieved on January 31, 2026 (GMT) from https://www.dejima-tokyo.com/articles/46/edo-tokyo

There are currently no comments on this article.