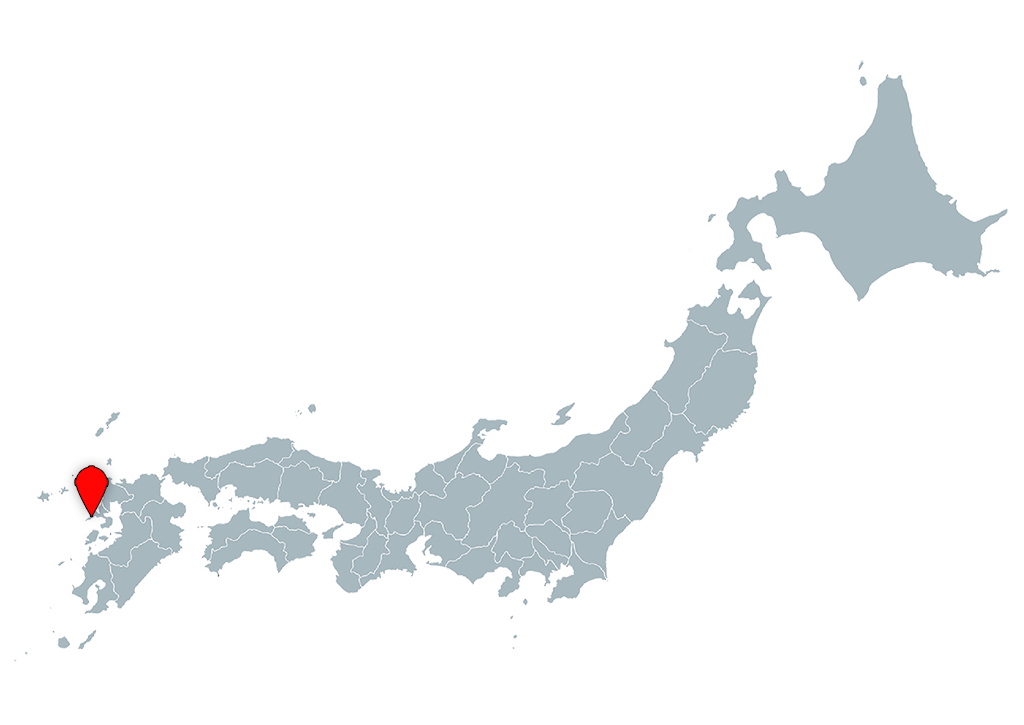

First diplomatic mission

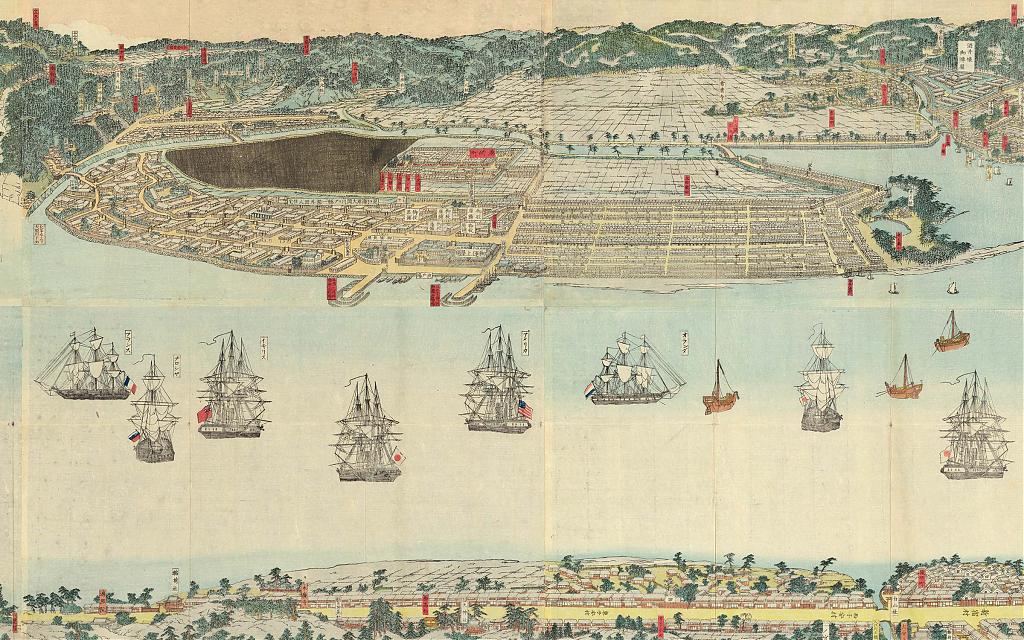

The Dutch trading station at Nagasaki’s Dejima island was run by a chief agent (or “Opperhoofd”) who was not a political representative.1 This changed in 1855, when the last Opperhoofd, Jan Hendrik Donker Curtius, received the title, “Dutch Commissioner in Japan.” As a result of this appointment, the residence of the Opperhoofd became the first Dutch diplomatic mission in Japan.

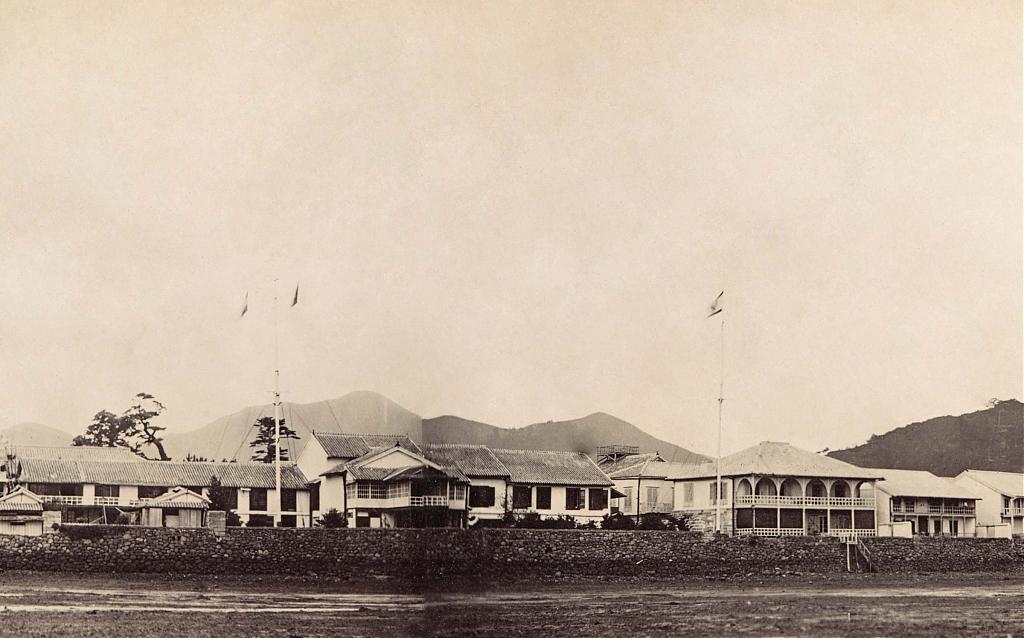

The two-storied Opperhoofd’s residence was located very close to the Water Gate, one of only two entrances to the island. Dutch naval officer Hendericus Octavus Wichers who lived at Dejima between 1857 and 1860, described the approach to the building in his diary:2

When one goes from the roadstead to Desima [sic], one enters that island through the Water Gate, a gate which was formerly open only during the unloading and loading of ships, but now remains open from morning to night and is only closed at night. Straight ahead, one now sees a fairly wide street, paved in the middle with large elongated stones. On the right side, first a Japanese guardhouse, intended for the officer of the watch who is always there when there are Japanese, coolies, and workmen at Desima. We call him Opperbanjoo[s]t. Next, an empty house formerly occupied by the Master of the Storehouse, then the house of the Opperhoofd.

Wichers writes that the houses at Dejima were built using traditional Japanese construction methods. They were timber framed with walls made of bamboo, tied up with rice straw ropes, and plastered with clay. “Inside, the wall is covered with beautiful Japanese wallpaper, all the pieces a foot long and a half wide. The outside is covered with an excellent kind of white plaster, or with thin planks which are then painted black.”3

Because a devastating fire had destroyed most of the buildings on Dejima in 1798, the Opperhoofd’s residence was still fairly new when Donker Curtius arrived in 1852. It had only been completed in 18094, and appears to have been remodeled just before the arrival of Opperhoofd Pieter Albert Bik in 1842.5 Ten years later, it must still have been in a good state of repair.

Bik, who left Dejima in 1845, took a floor plan of the residence back with him to the Netherlands. So, we know how the building was used around that time. Most likely, little had changed when it became the Dutch diplomatic mission in 1855.

The floor plan shows large reception and guest halls, an office, a veranda from which incoming ships could be seen, and several private rooms, including a room for the courtesan (meidkamer). It was conveniently situated right next to the bedroom.

As was custom at Dejima, all these rooms were located on the second floor of the building. The ground floors were generally used as storage space.

Wichers, who used the residence to teach modern navigation to some thirty Japanese students, writes that it was “very spacious, and partially very decently furnished at government expense for the reception of important people, like lords, governors, etc. In one of the rooms the entire Royal family is on display in ornately gilded frames.”6

Sayonara Dejima

In 1859, once again, many buildings were destroyed by fire. The well was dry and it was low tide, so there was no water for firefighting. The flames were finally stopped because some 200 Russian sailors who had rushed in to help knocked down an old house.7

Thanks to them, the Opperhoofd’s residence survived the disaster. On a map that Wichers drew of Dejima, the houses that burned down are marked in red. It graphically illustrates that the fire came within meters of the residence.

Consul General Jan Karel de Wit gratefully took advantage of this miracle when he took over from Donker Curtius in 1860, only a year after the fire. He moved into the former Opperhoofd’s residence and made it the consulate general. When he left Japan in 1863, the consulate general was moved to Yokohama. The government furnishings that so impressed Wichers, were moved to the new location as well.

Around this time, merchants of other nationalities were starting to make Dejima their new home, while the unique position of the Netherlands in Japan was quickly fading. Following more than two centuries of continuous use, the curtain had finally closed on Dejima as a unique and exclusive Dutch home base in Japan.

After the consulate general was moved away from Nagasaki, the agent of the Netherlands Trading Society (Nederlandsche Handel-Maatschappij), Albert Bauduin, was appointed consul. He moved into the former Opperhoofd’s residence, which now became the Dutch consulate.

The Dutch government auctioned off the former Opperhoofd’s residence on January 16, 1865.8 Bauduin became the leaseholder. He moved to Kobe in January 1868, after which consular affairs were taken care of by succeeding employees of the Netherlands Trading Society.

It appears that the consulate remained in the former Opperhoofd’s residence through December 16, 1874, when Consul Johannes Jacobus van der Pot handed consular services over to Marcus Octavius Flowers, the consul of Great Britain.9 In a letter dated January 5, 1875, Van der Pot wrote that the flagpole of the consulate at Dejima had been moved off the island to the Netherlands Trading Society office at number 5 in the foreign settlement of Oura.10 A truly symbolic farewell.

Over the next three decades, Dutch consular affairs were taken care of by a succession of merchants and consulates of other countries as Nagasaki became increasingly irrelevant to the Netherlands.

Acting consul Müller-Beeck reported in 1890 that not a single Dutch merchant ship had visited Nagasaki port during the previous year. There were now only seven Dutch nationals living in the city, even fewer than the dozen or so that lived on Dejima when Japan was still a closed country.11 He listed a mere 12 entries in the ledger for the financial year ending in July 1890, spending a meager 7.79 dollars on consular expenses.12

Dutch consular responsibilities were handed over to the British consulate at 6 Oura in 1908. The end came in 1941. When Pearl Harbor was attacked by the Japanese on December 8, British Consul Ferdinand Cecil Greatrex was the acting vice-consul for the Netherlands.

Japanese military police surrounded the consulate, placed Greatrex and his wife Margaret under house arrest and later confined them to a school on the outskirts of Nagasaki. In July 1942, they were finally allowed to return to the United Kingdom on an exchange ship.

After the end of the Second World War, Nagasaki only hosted an honorary vice-consulate and consulate. The centuries-long Dutch presence had now become a distant memory. Even Dejima itself had vanished, swallowed up by reclamation work.

| TIMELINE | |

|---|---|

| 1852 | Jan Hendrik Donker Curtius becomes the new Opperhoofd at Dejima. |

| 1855 | Opperhoofd Jan Hendrik Donker Curtius is appointed "Dutch Commissioner in Japan." The Opperhoofd's residence becomes the first Dutch diplomatic mission in Japan. |

| 1860 | Consul General Jan Karel de Wit arrives. The former Opperhoofd's residence becomes the first Dutch consulate general in Japan. |

| 1863 | The consulate general is moved to Yokohama. The former Opperhoofd's residence now becomes a consulate. Albert Bauduin, agent of the Netherlands Trading Society, becomes consul. |

| 1865 | The former Opperhoofd's residence and the former chancellor's building, are sold at auction for a sum of 4250 Mexican dollars. |

| 1874 | Consular services are transferred to the British consul on December 16, likely the last date that the former Opperhoofd's residence is used as the consulate. |

| 1941 | The British consulate is closed after the December 8 attack on Pearl Harbor. The Dutch consular presence in Nagasaki comes to an end. |

Next: 3. Kanagawa-Yokohama

What we still don’t know

(These questions are only shown on this site)

- Which consuls were honorary or vice-?

- What were the addresses after the consulate moved out of Dejima? Only the address of the British consulate taking care of Dutch interests is known.

Notes

- Footnotes are only shown on this site, not in the book.

- See the Notebook of this article for the raw data.

- See the Archive for some of the primary documents used in the study.

1 Dutch trade relations were based on a document that Shōgun Tokugawa Ieyasu had given to Dutch merchants in 1605. The first dutch trading station was set up at Hirado in Nagasaki. The Dutch were moved from Hirado to Dejima in 1641. The Dejima trading post was administered by a chief agent (Opperhoofd), since 1800 appointed by the Dutch colonial government in Batavia. Officially, the Opperhoofd was not a diplomatic representative of the Netherlands.

2 Wichers, Hendericus Octavus. Oorzaken der komst van een detachement van de Koninklijke Nederlandsche Marine in Japan, 1855-1860, B II 108 A, National Maritime Museum Amsterdam, 22.

3 ibid, 23.

4 Nagasaki City Council on Improved Preservation at the Registered Historical Site of Deshima (1987). Deshima: Its Pictorial Heritage, Nagasaki City, 296.

5 ibid, 297.

6 Wichers, Hendericus Octavus. Oorzaken der komst van een detachement van de Koninklijke Nederlandsche Marine in Japan, 1855-1860, B II 108 A, National Maritime Museum Amsterdam, 11–12.

7 ibid, 92.

8 Algemeen Handelsblad. Amsterdam, March 4, 1865, pp. 2. Also Nationaal Archief. 2.05.10.08 Inventaris van het archief van het Nederlandse Gezantschap in Japan, 1879-1890, 28: 0734 and 0736.

9 Nationaal Archief. 2.05.10.08 Inventaris van het archief van het Nederlandse Gezantschap in Japan, 1879-1890, 29: 0451.

10 Nationaal Archief. 2.05.10.08 Inventaris van het archief van het Nederlandse Gezantschap in Japan, 1879-1890, 36: 0009.

11 Nationaal Archief. 2.05.10.08 Inventaris van het archief van het Nederlandse Gezantschap in Japan, 1879-1890, 28: 0255.

12 Nationaal Archief. 2.05.10.08 Inventaris van het archief van het Nederlandse Gezantschap in Japan, 1879-1890, 28: 0251.

REFERENCE IMAGES

The following images are not used in the book.

Published

Updated

Reference for Citations

Duits, Kjeld (). 2. Nagasaki, From Dejima to Tokyo. Retrieved on January 31, 2026 (GMT) from https://www.dejima-tokyo.com/articles/41/nagasaki

There are currently no comments on this article.