A new port

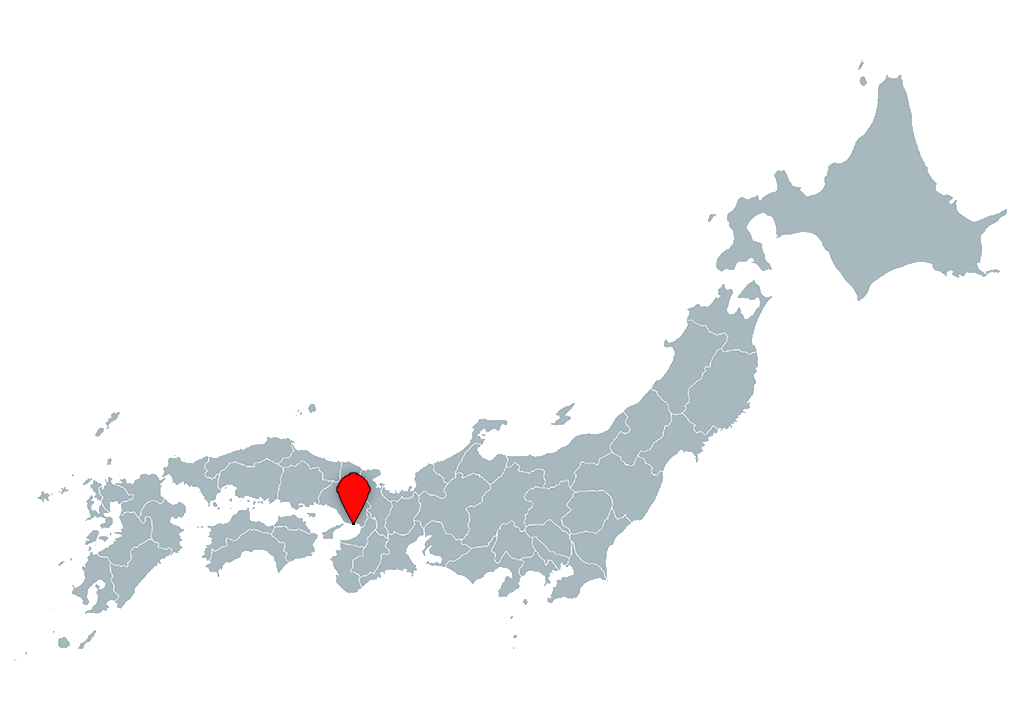

On January 1, 1868, the port of Hyogo (present-day Kobe)—a narrow strip of land squeezed in between the Rokko mountain ridge and Osaka Bay—was opened to international trade. The moment was celebrated by a “thunderous roar of the guns of 12 English, 5 American and 1 French warship,” wrote Consul General De Graeff van Polsbroek in a letter to the Dutch Minister of Foreign affairs.1

At noon, the English, American and French flags—no Dutch warship was present—were saluted with 21 rounds by the Japanese warship Kaiyō Maru (開陽丸), a three-masted, steam-powered frigate built in the Netherlands. These salutes were in return answered by the guns of the foreign warships.

The people in the area seemed to have been happy about the opening. “The Japanese inhabitants of this place walked through the streets of the city in their festive garb, singing and dancing, and proved by their clamor how much it pleased them that the city had been opened to foreign trade,” wrote the consul general.

Perhaps they were celebrating the outrageous rents they were able to charge. According to De Graeff van Polsbroek’s letter, one month’s rent was equal to a third of the value of the house. In an anonymous letter published by Dutch daily Nieuwe Rotterdamsche Courant, a Dutch merchant wrote that a month’s rent was equal to the total purchase price.2

The merchant had no choice but to pay the exorbitant rent, because no housing had yet been built for the foreign merchants and diplomats. The promised foreign settlement was just an empty sandlot.

We flattered ourselves in the hope that the Japanese government would have built some houses for us, and warehouses for our merchandise, so we would have safe shelter for the time being. But we were sorely disappointed, because except for a half-completed customs house, nothing had been prepared for our arrival. With all our belongings, we literally stood on an empty beach.

First consulate in Kobe

Notwithstanding this lack of housing, De Graeff van Polsbroek was able to inform the Minister of Foreign Affairs that “a very good temple” had been arranged for Consul Albertus Johannes Bauduin (1829-1890), chief agent of the Nederlandsche Handel-Maatschappij (Netherlands Trading Society or NHM). The Dutch flag was immediately hoisted there.

De Graeff van Polsbroek does not name the temple, but the research for this book strongly suggests that it was Zenshōji (善照寺). This was a large temple of distinction located on the Saigoku Kaidō Road (西国街道), the important highway that connected the ancient capital of Kyoto with Shimonoseki, at the western end of Honshu Island.3

Zenshōji stood at a central location, right behind the former Kobe Village Assembly, which was temporarily used as the Meiji Government’s foreign affairs office after it came to power in early 1868. Japanese politician and statesman Itō Hirobumi4 often visited here when he was governor of Hyogo Prefecture (1868–1869). The buildings were located at what is now Motomachi 3-chome, relatively close to Motomachi Station.

On February 4, hundreds of soldiers of the Bizen domain marched past this building just before a violent altercation between them and the inhabitants of the foreign settlement took place near Sannomiya Shrine. The incident created a crisis that caused the nations with consulates in Kobe to briefly occupy the city with their military forces and seize Japanese warships in the harbor.

It was the first major international incident that the imperial court faced as it began to take over power from the Tokugawa shogunate during the Meiji Restoration. The crisis was ultimately defused when a Bizen officer, Taki Zenzaburo, was forced to commit ritual suicide at Eifukuji Temple on March 3.

Dutch Chancellor Leonardus Theodorus Kleintjes, who attended the execution together with the secretaries of the other foreign legations, wrote a sober report. After a factual description of the people who were present, and the interior of the temple, he described the seppuku ritual suicide.5

The convict was 30 to 34 years of age, of strong physique and had a good appearance and medium stature. His clothing consisted of a white undergarment, a black outer garment, a blue ceremonial cloak and dark pants. No sooner was he seated, or one of the executioners brought him a small white pinewood wooden table, on which lay a short Japanese sword in a white paper sheath. When this was in front of him, he made a short speech with a trembling voice and a highly affected and moved expression, in which he announced that he was the person who on the 11th day of the 1st Japanese month had given orders to the soldiers under his command to fire on the foreigners, and that he would now, as atonement for this act, cut his abdomen. After having said this, he stripped himself to the middle of his clothes, took the short sword in his hand and stabbed himself in the abdomen, which made him assume a somewhat stooped posture. At the same time, the executioner, who had waited with a raised unsheathed sword behind the back of the condemned person for the moment when some blood would gush from the wound, delivered the blow and separated the head from the torso in a single cut.

The incident was extremely important in that it demonstrated to the foreign representatives, who all happened to be in Kobe and had actually ducked the bullets of the Bizen troops, that power had effectively been transferred from the shogun to the emperor.

Even more significant was that the new government agreed to the execution demanded by the foreign representatives. This told the diplomats of the foreign powers that the Meiji government intended to change its policy from expelling foreigners (攘夷, jōi) to establishing friendly relations (開国和親, kaikoku washin) long before this policy change was made official. The first public proclamation that the emperor would fulfill the foreign treaties would not be announced until late March.

It was a historically significant start for the fledgling Dutch consulate.

Planting roots

Around May, when the dust had settled in the area, the consulate and NHM office were moved to a Western style house on Ikuta no Baba, originally a beautiful tree-lined road leading from the beach to Ikuta Jinja Shrine.6 According to the Nihon Shoki, the second-oldest book of classical Japanese history, this shrine was founded by Empress Jingū at the beginning of the 3rd century AD. A rather illustrious location for the new consulate.

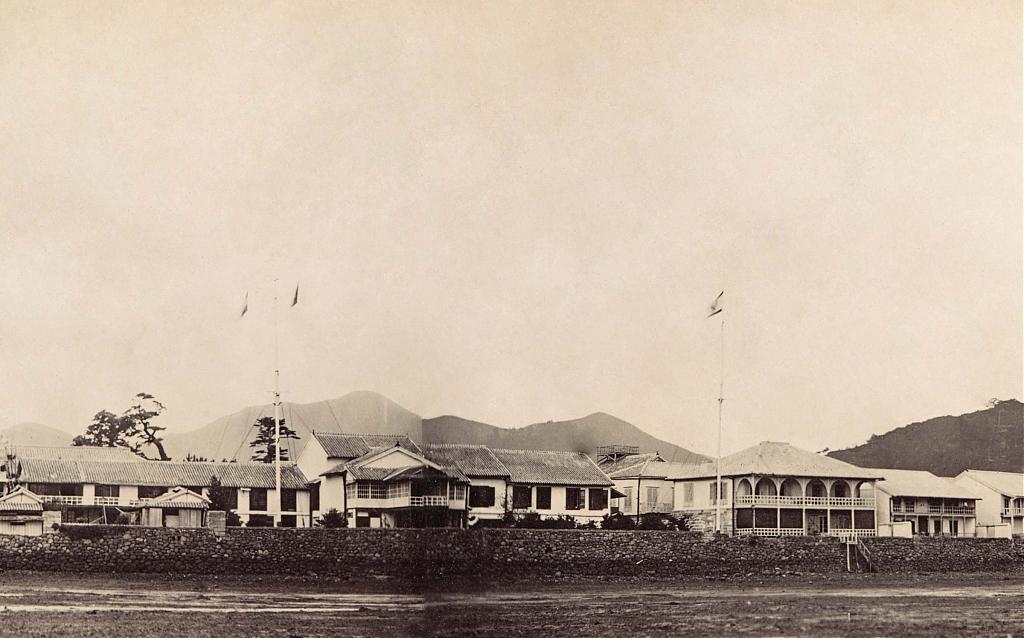

The house, which interestingly was located just outside the boundaries of the foreign settlement, was built by Evert and Marten Caspar Bonger, two brothers from Amsterdam. They rented it to NHM. No description of the premises has yet been found, but this study has for the first time identified photographs showing the building.7

The foreign settlement’s first land auction was held on September 10. NHM purchased one of the best plots, number 5 on Kaigandori, the avenue fronting the harbor which was also known as the Bund.8 The large plot was located conveniently near Kobe’s main pier and not too far from the customs house. Dutch captains and merchants would not have to walk too far to get business done.

An NHM warehouse was nearing completion here around May 6 of the following year, while the framework for a residence and an office were being erected around October 27.9 These were “two substantial stone buildings” reported the Hiogo News.10

Around May 1870, almost two and a half years after the opening of the port, the consulate finally moved to its exclusive new location on the Bund.11

The merchant inhabitants of Japan’s foreign settlements were mesmerized by Ionic and Corinthian capitals, Palladian arches, pilasters, dentils and broken pediments.12 The building used as the Dutch consulate and the head office of NHM generally followed this pattern.

The consulate was a typical two-story stone and wooden treaty port building with a pillared corner porch covered with a roof overhang. A second-floor balcony overlooked the Bund, while another balcony on the Japanese tiled roof offered an unobstructed view of Kobe Harbor.

It is unknown who designed the building. But because of the close connections between Consul Bauduin and the Bonger brothers, who advertised as architects, it is likely that the house was built and designed by them.

The consulate is believed to have remained at this address until around 1877.

It turned out to have been extremely well-chosen. Over the next century, the German, Italian and American consulates would also use this lot, as well as the Kobe office of one of the largest shipping companies in Japan, Osaka Shosen Kaisha (OSK), now known as Mitsui O.S.K. Lines. The influential Hongkong and Shanghai Bank, the present HSBC, moved into nearby number 2 in 1881, while the famed Oriental Hotel moved to the neighboring plot, number 6, in 1907. Many world-famous people would stay here, including American actress Marylin Monroe.

Moving around

Between 1878 and the early 1920s, the consulate constantly moved. It was located at no less than twelve addresses, after which it finally settled in the Crescent Building, a modern office building at 72 Kyomachi.

It would become the last building in Kobe to house a Dutch consulate. In 1928, Dutch envoy Jean Charles Pabst wrote a letter to the Dutch Minister of Foreign Affairs arguing that the Kobe consulate should become a consulate general.

Around this time, Japan’s trade with the Netherlands East Indies (present-day Indonesia) was increasing rapidly. It ranked fifth in the list of countries that Japan exported to, while ranking eighth for imports. The Dutch consular representation in Japan, “a consulate in Kobe for the whole of Japan, and a vice-consulate in Yokohama for this port and its surroundings,” no longer represented the importance of the Netherlands, wrote Pabst:13

Countries far less important to trade from and to Japan than we are, e.g. Argentina, Mexico, Chile, Bolivia, Columbia, Romania, Italy, have a consulate general in this country; even Luxembourg has followed suit. In Yokohama, the Dutch vice-consulate is the only one of its kind; countries like Greece, Guatemala, Peru and Portugal have a consulate there. Such a consular office may be a superfluous luxury for countries like the ones mentioned above, but for a country like ours it is certainly not; Japan’s growing importance for our export trade gives us the same significance as France, Germany and Italy have. If our consular representation does not accord with this, as it does at present, our interests and prestige suffer; especially in Oriental countries — and Japan is still Oriental in this respect — it makes a painful and damaging impression that on official occasions our consular representative at Yokohama always comes last, while at Kobe he has to give precedence to consuls general of countries such as Argentina, Columbia and Italy. Furthermore, I feel I must draw attention to the fact that Japan is the only major power where we do not have a consul general. They are not insensitive to this sort of thing here, especially since we do have consuls general in other places in the Far East and in Australia.

Pabst’s argument carried the day. In 1930, the Consulate of the Netherlands in Kobe became the Consulate General for Japan and Kwantung (the leased territory of the Empire of Japan in the Liaodong Peninsula).14

Because the space at the Crescent Building was too small and noisy, the consulate general moved to a three-room office in the Meikai Building (明海ビルディング) at 32 Akashimachi in December of that year.15

The multi-story Meikai was one of the best office buildings in Kobe, and easily accommodated the expanding consulate general. Over the next decade, the office doubled from three to six rooms: the consul general’s room, the consul’s room, a general office, rooms for the interpreter and secretary, and a drawing and store room.16

It remained at the Meikai until the Second World War forced its closure. The Japanese authorities sealed the consulate general on December 13, 1941.17

Sweden now assumed the task of being the Protecting Power of the Netherlands and became its diplomatic representative in Japan. On February 25, 1942, Consul General Johan Burchard Diederik Pennink transferred the “archives and other properties” of the consulate general to Swedish consul Lorens Wirén.18 Pennink, his wife, Consul Nicolaas Arie Johannes de Voogd, and two other consulate officials were interned at the Pennink residence until they were evacuated on July 30.19

As the Meikai Building was just around the corner from the consulate’s first location inside Kobe’s foreign settlement in 1870, number 5 on the Bund, the closing somehow feels symbolic. The consulate had moved all around the settlement, and a few locations outside, and then returned close to its starting point inside the settlement. As if an imaginary circle was completed.

A new beginning

The Japanese empire surrendered on August 15, 1945, and the allied occupation of Japan began two weeks later. As a result, Sweden ceased to represent Dutch interests in Japan some ten months later, on June 20, 1946.20

This left a gap. There was a need for Dutch representation in the region around Kobe and Osaka, but General Headquarters of the Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers (GHQ) did not allow “formal consular offices” or the “formal functioning of consular officials.” So instead, a temporary representative of the Netherlands Military Mission for Western Japan, C. W. Brand, was appointed in early September.

GHQ however specifically stressed that “it is understood that neither the Mission nor its branch in Kobe will have direct official relations with local Japanese Government officials, and that all matters requiring communication with the Imperial Japanese Government will be cleared through the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers.”21

On October 8, 1946, acting Swedish Consul Per Björstedt transferred the remaining “documents and archives” of the consulate general to Brand.22 An office was set up at 139 Yamamoto-dori 3-chome. This was soon moved to number 150.23 In 1947, the facade of this office, complete with Brand’s military jeep, was immortalized in a painting by renowned Kobe based artist Komatsu Masuki.

The consulate remained at this address for several years. It then temporarily moved to the office of the Nationale Handelsbank at the Bank of Tokyo Building at 24 Kyomachi in the old settlement, sometime before 1951.24

By 1951, things had markedly improved in Japan. Dutch envoy Petrus Ephrem Teppema wrote a letter to the Minister of Foreign Affairs arguing that “the growth and scope, as well as the nature of the Dutch economic interests in Japan make it necessary, in my opinion, to once again place a consul general in Kobe/Osaka (the Kansai area).” He wrote that not to do so “would be irresponsible.” Teppema believed that a consulate general in Kobe had to be seen “as comparable in importance to the consulates general in Sidney, Singapore, Hong Kong, or San Francisco.”25

One month before the restoration of diplomatic relations between Japan and the Netherlands on April 28, 1952, the president of Kobe City council stated a similar case in a letter requesting the reopening of the consulate general.26 The Hague listened. On June 17, 1952, W. H. de Roos arrived in Kobe to become the first post-war consul general.27

It is believed that the office returned to the Meikai Building around this time.28 Around 1957, it was moved to the 5th floor at the Denden Building at 64 Naniwa-chō, Ikuta-ku.29 It would stay here through 1977, after which it moved to the 20th floor of the Kobe C.I.T. Building at 5-1-14 Hamabedori, Fukiai-ku.30

Farewell

In the early morning of January 15, 1995, a major earthquake devastated Kobe and surroundings. The Kobe C.I.T Center Building survived the disaster, but the consulate general had been shaken to its core. Press and culture officer Hans Kuijpers was the first to enter the office. He was shocked. “It was a huge mess. The office was strewn with paper and things that had fallen over. Nothing was left standing. Even the safe had fallen over.”

The disaster became an unexpected turning point. Within several weeks, the office was moved to room 2726 at the Hilton Hotel in Osaka, across from Umeda Station, the busiest station in western Japan. Some three months later, it moved to its new location at Twin 21 MID Tower, right next to the iconic Osaka Castle.

After 127 years, Kobe was no longer home.

Osaka

Over the years the Dutch consulate in Kobe also covered Osaka. But when Kobe and Osaka were opened for international trade on January 1, 1868, separate consulates were actually established for each city.

Initially, Osaka seemed the bigger prize to merchants. It was much larger and was a well-developed merchant town. Thus it was important to have a consulate to support the Dutch merchants who decided to settle here.

But big ships could not enter the harbor—landing in Osaka was even life-threatening during stormy weather—and land prices were high. Merchants eventually realized that Kobe offered far better opportunities. But until this realization took hold, Osaka had its own consulate.

As in other cities, it was located at the local NHM office. NHM employee Pieter Eduard Pistorius became the vice-consul. He rented a residence of “one of the most prominent Japanese merchants,” wrote Consul General De Graeff van Polsbroek in a letter to the Minister of Foreign Affairs. Here he raised the Dutch flag.31

On January 21, Chancellor Kleintjes wrote in his diary that Pistorius moved into his own house at the Foreign Settlement at Kawaguchi.32 However, things did not start off well. Only six days later, a civil war started in Kyoto, a mere fifty kilometers away.

The hostilities reached Osaka within days. All the foreigners, including all the foreign diplomats, who happened to be in Osaka for talks with the shogun, were forced to retreat to Kobe. By mid-March, they were back in Osaka though, and the new consulate was in business.

Thanks to photographs taken by Dutch army physician and chemist Koenraad Wolter Gratama—today known as the founding father of chemistry in Japan—we know what the consulate looked like. The combined NHM lot and consulate was an almost fort-like collection of Japanese buildings, including several kura, traditional Japanese storehouses built from timber, stone or clay. The lot was located at Umemotocho, right on the edge of the settlement.

The NHM office was discontinued on June 30, 1874. Around this time, the consulate was moved to 4 Hakodate Yashiki where it was overseen by vice-consul Johann Carl Jacob Klein. It is believed that Hakodate Yashiki (箱館邸) was the area previously used by the Hakodate Products Distribution Center (箱館産物会所) in what is now 3-chome Utsubohonmachi (靱本町3丁目).33 The consulate remained here until about 1876, when the consular presence in Osaka was discontinued.

After 1995

Over the next 119 years, there was no Dutch representation in Osaka. The Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs briefly considered opening a separate consulate in Osaka in 1936, but deemed it unnecessary.34

This all changed in 1995, when the consulate general moved from Kobe to Osaka because of the earthquake.

The new office at the Twin 21 MID Tower was impressive. The high-rise office tower was one of the most prestigious addresses in Osaka, housing a number of blue-chip corporations and consulates general.

The consulate general was initially located at temporary premises on the 6th floor, but by December of 1995 a new office was completed on the 33rd floor. Staff moved into these new premises in early 1996. In November 1997, once again a major change took place when this office was greatly expanded.

The magnificent view of the vast city of Osaka and the beautiful interior left a strong impression on visitors. As it did on staff members, who would occasionally enjoy drinks in the consul general’s room on Friday afternoons.

After two decades at the Twin 21 MID Tower, change was once again in the air. The technological and social changes of the 21st century created new trends in the work place, which persuaded the government of the Netherlands to introduce a more flexible way of working, based on the concept of “Het Nieuwe Werken” (HNW, the new way of working). In this concept, open working spaces replaced individual offices.

This meant that far less space was needed. The consulate general therefore moved to the nine-story Kitahama 1-Chome Heiwa Building in Osaka’s Kitahama district in September, 2016. Located on the eighth floor of this long and narrow office building along the Tosaborigawa River, the consulate general has a beautiful view on both the river and Nakanoshima Park.

Although the consulate general was officially opened by Osaka Mayor Yoshimura Hirofumi on November 15, the first working day here was September 19.35

| TIMELINE | |

|---|---|

| 1868 | Consulates opened in Hyogo (present-day Kobe) and Osaka. |

| 1870 | The Kobe consulate moves to its first permanent location at number 5 on the Bund. |

| 1876 | Osaka consulate is closed. |

| 1930 | The Consulate of the Netherlands in Kobe becomes the Consulate General for Japan and Kwantung. |

| 1941 | Japanese authorities seal the consulate general on December 13 (World War II). |

| 1946 | A temporary representative of the Netherlands Military Mission for Western Japan, stationed in Kobe, is appointed. |

| 1952 | The consulate general is reopened. |

| 1995 | The consulate general is moved to Osaka after the Great Hanshin Earthquake. |

Next: 6. Other locations

Locations

| ADRESSES | |

|---|---|

| 01 Jan–May, 1868 | Zenshōji temple (善照寺) in what is now Motomachi 3-chome |

| 02 May 1868–May 1870 | Ikuta Baba, building owned by the Bonger brothers |

| 03 May 1870–±1878 | 5 Kaigandori (海岸道5番) |

| 04 ±1878–1897 | 91 Edomachi (江戸町91番) |

| 05 1897–1899 | 48 Nakayamate-dori Sanchome (中山手通3丁目48番) |

| 06 1900–1902 | Suwayama 3 Yamamoto-dori Gochome (山本通5丁目諏訪山3番) |

| 07 1902–1903 | 8 Nakayamate-dori Ichome (not yet located on map) |

| 08 1903–1909 | 45 Yamamoto-dori Nichome (山本通2丁目45番) |

| 09 1909 | 125 Kitano-cho Ichome (北野町1丁目125番) |

| 10 1910 | 12 Nakayamate-dori (中山手通12番) |

| 11 1911–1915 | 80 Kyomachi (京町80番) |

| 12 1915 | 78-B Kyomachi (京町78-B番) |

| 13 1916–1919 | 81 Kyomachi (京町81番) |

| 14 1919 | 76 Kyomachi (京町76番) |

| 15 1920–1922 | 28 Harimamachi (播磨町28番) |

| 16 1922–1930 | 72 Kyomachi, Crescent Building (京町72番 クレセントビルディング) |

| 17 1930–1941 | 32 Akashimachi, Meikai Building (明石町32番 明海ビルディング) |

| 18 1946 | 139 Yamamoto-dori 3 chome (山本通3丁目139番) |

| 19 1947–1950(?) | 150 Yamamoto-dori 3 chome (山本通3丁目150番) |

| 20 1951 | 24 Kyomachi Bank of Tokyo Building (京町24番 東京銀行ビル) |

| 21 1952–1956 | 32 Akashimachi, Meikai Building (明石町32番 明海ビルディング) |

| 22 1957–1977 | 64 Naniwamachi, Denden Building 5th Floor (浪花町64 電電ビルディング5階) |

| 23 1978–1995 | 5-1-14 Hamabedori, Kobe C.I.T. Building, 20th floor (浜辺通5-1-14 神戸商工貿易センタービル20階) |

| These addresses are contemporary and may differ from the modern address. Some years are approximate. See the locations on a Google Map. | |

What we still don’t know

(These questions are only shown on this site)

- Was the first post-war location indeed at 3-139 Yamamoto-dōri, or was this a private address only?

- When was the consulate moved from 3-139 Yamamoto-dōri to 3-150?

- When was the consulate moved from 3-150 Yamamoto-dōri to the Bank of Tokyo Building?

- When was the consulate moved from the Bank of Tokyo Building to the Meikai Building?

- When was the consulate general moved from the Meikai Building to the Denden Building?

Notes

- Footnotes are only shown on this site, not in the book.

- See the Notebook of this article for the raw data.

- See the Archive for some of the primary documents used in the study.

1 Nationaal Archief. 2.05.01 Inventaris van het archief van het Ministerie van Buitenlandse Zaken, 1813-1870, 3147: 0079–0080.

2 Nieuwe Rotterdamsche courant: staats-, handels-, nieuws- en advertentieblad. Rotterdam, March 25, 1868, pp. 1.

3 These findings are based on a letter by Political Agent and Consul-General Dirk de Graeff van Polsbroek, entries in an unpublished diary of Chancellor Leonardus Theodorus Kleintjes, a hand drawn map in the National Archives at Washington, and a document at Kobe University Library.

- De Graeff van Polsbroek writes in Januari 1868 that the Dutch Consul had been assigned a “very good temple”: “Aan den Consul der Nederlanden te Hiogo werd op mijn verzoek een zeer goede tempel ter bewoning afgestaan en aldaar onmiddellijk de Nederlandsche vlag geheschen.” He does not mention the name of the temple, but “very good” limits it to just a few. Nationaal Archief, Netherlands, 2.05.01 Inventaris van het archief van het Ministerie van Buitenlandse Zaken, 1813-1870, 3147 1868-1870, 0080, January 6, 1868, De Graeff van Polsbroek at Hyogo.

- On February 20, 1868, Chancellor Kleintjes writes in his diary that he moved in with Kobe Consul Bauduin. He reports on March 12 that he arrives at the “Dsjendsjoodsjie” temple, the Zenshōji (善照寺), in Kobe, after his return there from a one week stay in Osaka. On his return he was met bij Bauduin when he was close to Kobe. The walks that Kleintjes describes in his diary are all feasible from Zenshōji, and repeatedly include Bauduin. Diary of the Dutch diplomat and commissionaire Leonardus Theodorus Kleintjes, 1867-1870, TY92058899, International Research Center for Japanese Studies.

- A hand drawn map of Kobe dated February 1868 has “Dutch Consulate” written at the approximate location of Zenshōji. National Archives, Washington. Despatches from U.S. Ministers to Japan, 1855-1906 Item: Jan. 2, 1868 – Apr. 8, 1868, 127.

- In the list of documents about the opening of Kobe Port at the Kobe University Library, there is a document dated March 11, Keio 4 (April 3, 1868) mentioning four Japanese individuals and the “Dutch Consul” at Zenshōji in Kobe in regards to a “lodging notification” (止宿届書). Kobe University Library, G2-0696 行政-願書・要望・請願伺届.

- On page 5 of History of Kobe by Gertrude Gozad, published in The Japan Chronicle, Jubilee Number 1868-1918, it is mentioned that the French consulate was initially located at Ikuta shrine, ruling this location out as the “very good temple” used by the Netherlands.

- Incidentally, Willem Conrad Korthals, who arrived in Kobe on January 1, 1868 and who became vice-consul and later succeeded Bauduin as consul, purchased a large piece of land right behind Zenshōji to build his residence. One wonders if he became acquainted with the plot and the owner because he stayed at the nearby temple. The lot was later purchased from Korthals by Hyogo Prefecture and used as the Hyogo Prefectural Office (Kenchō). It is now Hyōgoken Kōkan (兵庫県公館), also known as Hyogo House.

4 伊藤 博文, 1841–1909.

5 Nationaal Archief. 2.05.01 Inventaris van het archief van het Ministerie van Buitenlandse Zaken, 1813-1870, 3047: 0202–0203. “De veroordeelde was van 30 tot 34 jarigen leeftijd, van sterken lichaamsbouw en had een goed uiterlijk en eene middelmatige gestalte. Zijne kleding bestond in een wit onderkleed, een zwart bovenlaag, een blauwe ceremonie mantel en een donkere broek. Nauwelijks was hij gezeten of een der scherpregters bracht hem een klein wit greenen houten tafeltje, waarop een korte Japansche sabel in wit papieren schede was gelegen, toen dit voor hem stond hield hij met bevende stem en eene in hooge mate aangedane en bewogen gelaatsuitdrukking eene korte aanspraak, bij welke hij te kennen gaf, dat hij de persoon was, die den 11en dag der 1e Jap. maand aan de onder zijn bevel staande soldaten last had gegeven om op de vreemdelingen te Kobe te vuren en dat hij zich thans, voor boeting dezer daad, den buik zou snijden. Na dit gezegd te hebben ontblootte hij zich tot aan het middel van zijne kliederen, nam de korte sabel in de hand en gaf zich een steek in den buik, welke hem eene eenigzints gebogen houding deed aannemen, gelijkertijd bracht de scherpregter, die met een opgeheven blank zwaard achter den rug der veroordeelden het ogenblik had afgewacht waarop enig bloed uit de wonde spoot, den slag toe en scheidde in een houw het hoofd van den romp.”

6 The period when the NHM office and consulate were located at Ikuta no Baba has become clear from a rental agreement, a contemporary Japanese map, and ads placed in local newspaper The Hiogo News:

- One of the Bonger Brothers rents a house, and half of a storage house, on March 18, 1868.

- The 開港神戸之図 map locating the Dutch Consulate at Ikuta no Baba dates from the fourth month of Keio 4. This would be end April through May 1868 on the Gregorian calendar.

- May 6, 1869: European house occupied by NHM (The Hiogo News, May 6, 1869, pp 367)

- Mar 9, 1870: Ad: To Let. The House with Outhouses, at present occupied by H.N.M Consul, on the Temple Road. Apply to Bonger Bros. Next Door. Hiogo, March 9th, 1870. (The Hiogo News, March 16, 1870, pp. 35)

7 This study has also identified a photo held by Kobe City Museum which shows the consulate building. Until now the location of this photo was unknown.

8 The Japan Gazette, Sep 25, 1868, pp. 5.

9 May 6, 1869: Stone godown approaching completion (The Hiogo News, May 6, 1869, pp 367)

10 October 27, 1869: Stone Godown completed, “framework erected of two substantial stone buildings”—one a bungalow, to be used for residence, the other for business premises, etc. (The Hiogo News, October 27, 1869, pp 530)

11 May 25, 1870: Notice: Messr. Alt & Co. have removed their Offices to the premises lately occupied by the Netherlands Trading Society. Hiogo, 25th May, 1870 (The Hiogo News, May 25, 1870, pp. 167)

12 Finn, Dallas (1995). Meiji Revisited: The Sites of Victorian Japan. New York, Tokyo: Weatherhill, pp. 66.

13 Nationaal Archief. 2.05.38 Inventaris van het archief van het Ministerie van Buitenlandse Zaken: B-dossiers (Consulaire- en Handelsaangelegenheden), (1858) 1871-1940 (1955) [Stukken betreffende personeel en werkzaamheden van de Nederlandse consulaire vertegenwoordigingen in Japan]: 1372 Kobe, 1921 – 1940, 0320–0321.

14 ibid, 0291.

15 Nationaal Archief. 2.05.115 Inventaris van het archief van het Nederlandse Gezantschap in Japan (Tokio), 1923-1941: 108 Kobe, 1923-1937, 0143, 0144, 0146.

16 Nationaal Archief. 2.05.116 Inventaris van het archief van de Nederlandse diplomatieke vertegenwoordiging in Japan (Tokio), 1946-1954: 327 Stukken betreffende de overname van het archief en andere eigendommen door de Nederlandse vertegenwoordiging te Kobe in bezit van de Zweedse consul 1946, 0017–0026.

17 ibid.

18 ibid.

19 Lottaz, Pascal, Ottosson, Ingemar, Edström, Bert (2021). Sweden, Japan, and the Long Second World War: 1931–1945. 218.

20 Nationaal Archief. 2.05.116 Inventaris van het archief van de Nederlandse diplomatieke vertegenwoordiging in Japan (Tokio), 1946-1954: 421 Stukken betreffende het Nederlandse consulaat-generaal te Kobe 1946-1953, 0088.

21 ibid, 0086.

22 Nationaal Archief. 2.05.116 Inventaris van het archief van de Nederlandse diplomatieke vertegenwoordiging in Japan (Tokio), 1946-1954: 327 Stukken betreffende de overname van het archief en andere eigendommen door de Nederlandse vertegenwoordiging te Kobe in bezit van de Zweedse consul 1946, 0005.

23 A letter of the Head of Mission J.B.D. Pennink to Brand is addressed 139 Yamamoto-dori 3 chome. Nationaal Archief. 2.05.116 Inventaris van het archief van de Nederlandse diplomatieke vertegenwoordiging in Japan (Tokio), 1946-1954: 421 Stukken betreffende het Nederlandse consulaat-generaal te Kobe 1946-1953, 0074.

Nationaal Archief. 2.05.116 Inventaris van het archief van de Nederlandse diplomatieke vertegenwoordiging in Japan (Tokio), 1946-1954: 315 Stukken betreffende de behuizing van het Nederlandse missiepersoneel in Tokio 1946-1951, 0024 mentions 150 Yamamoto-dori 3-chome in Kobe. This information is undated.

In an interview by Kjeld Duits, the painting by Komatsu Masuki was identified by a former neighbor of the consulate as having been located at number 150.

150 Yamamoto-dori 3-chome is also the address given for the “Netherlands Military Mission in Japan, Kobe Branch” in the Directory of Trade and Industry, published by the Directory Committee of Hyogo Prefecture, Kobe, Japan in 1948.

24 Kobe Directory of Foreign Firms 1951.

25 Nationaal Archief. 2.05.116 Inventaris van het archief van de Nederlandse diplomatieke vertegenwoordiging in Japan (Tokio), 1946-1954: 421 Stukken betreffende het Nederlandse consulaat-generaal te Kobe 1946-1953, 0034–0037.

26 ibid, 0028.

27 ibid, 0020.

28 The Kobe Business Directory of 1953 and 1956, and the Kobeshi Shōkō Meikan (神戸市商工名鑑) of 1954 give the Meikai Building as the address.

29 Current address: Sannomiya Denden Bldg., 64 Naniwamachi, Chuo-ku, Kobe (〒650-0035 兵庫県神戸市中央区浪花町64・三宮電電ビルディング).

30 Current address: Kobe C.I.T Center Building, 5-1-14, Hamabedori, Chuo-ku, Kobe 651-0083 (〒651-0083 兵庫県神戸市中央区浜辺通5丁目1−14・神戸商工貿易センタービル).

31 Nationaal Archief. 2.05.01 Inventaris van het archief van het Ministerie van Buitenlandse Zaken, 1813-1870: 3147 1868-1870, 0121.

32 Diary of the Dutch diplomat and commissionaire Leonardus Theodorus Kleintjes, 1867-1870, TY92058899, International Research Center for Japanese Studies. 川口梅本町

33 This is based on research that Funakoshi Mikio (船越幹央) of the Osaka Museum of History (大阪歴史博物館) conducted for this study. The Hakodate Products Distribution Center (箱館産物会所) was located at Kensaki-machi (剣先町) from 1858 (Ansei 5) to 1872 (Meiji 5). The location was very close to the Foreign Settlement at Kawaguchi. Interestingly, currently the consulate general of the People’s Republic of China is located in this area.

34 Nationaal Archief. 2.05.115 Inventaris van het archief van het Nederlandse Gezantschap in Japan (Tokio), 1923-1941: 108 Kobe, 1923-1937, 0001–0002.

35 Kitahama 1-Chome Heiwa building 8B, 1-1-14 Kitahama, Chuo-ku, Osaka (大阪府大阪市中央区北浜1-1-14 北浜一丁目平和ビル8B). The Consulate-General moved to its new address between September 15 and 18, 2016. The first working day was September 19. The Consulate-general was officially opened by Osaka Mayor Hirofumi Yoshimura (吉村 洋文, 2015–2019) on November 15, 2016.

REFERENCE IMAGES

The following images are not used in the book.

Published

Updated

Reference for Citations

Duits, Kjeld (). 5. Kobe-Osaka, From Dejima to Tokyo. Retrieved on January 31, 2026 (GMT) from https://www.dejima-tokyo.com/articles/45/hiogo-kobe-osaka

There are currently no comments on this article.